Interview

“To Be Afflicted with Consciousness”

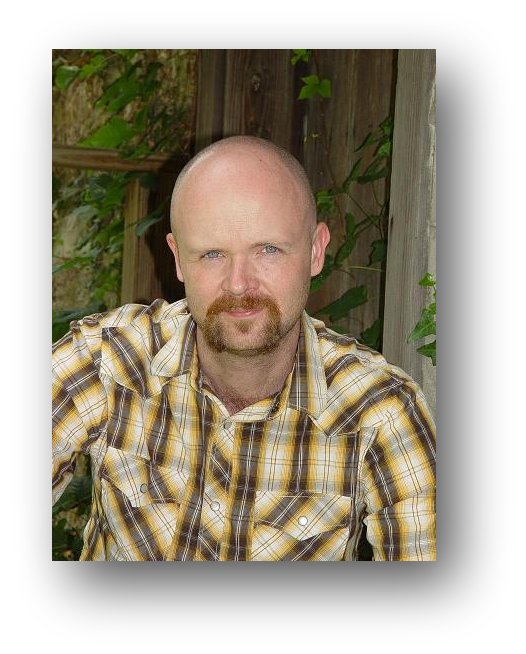

Charles Dodd White on Writing

Charles Dodd White describes his writing as being “about the people in and around the southern Appalachian Mountains, both in the past and present.” Within the span of about a year, Charles has produced three books, all of which, we predict, will become part of the Appalachian canon. His novel, Lambs of Men, was published in 2010; his short story collection, Sinners of Sanction County (2011), and the contemporary Appalachian fiction anthology, Degrees of Elevation (2010), were released by Bottom Dog Press through their New Appalachian Writing Series. Sinners of Sanction County has been nominated for the major Appalachian Book Prize, the Weatherford Award.

Charles was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1976. He currently lives in Asheville, North Carolina, where he teaches English at South College, and is on the creative writing staff of the Hindman Settlement School's Appalachian Writers Workshop. He has been a Marine, a fishing guide and a journalist. In 2011 Charles was awarded a fellowship in prose from the North Carolina Arts Council. His fiction has appeared in Appalachian Heritage, The Collagist, Fugue, Night Train, North Carolina Literary Review, PANK, Word Riot and several others. He also frequently contributes to Rain Taxi Review of Books.

Still: Can you tell us a little about your upbringing—when, where, how—and perhaps how that upbringing helped lead you to a writing career?

Charles Dodd White: I grew up spending a lot of time in the woods, mainly hunting and working chores that supported the deer camp in some way—clearing brush, hauling timber, etc. I was subject to the beauty of nature and also its violence. There were also stories, campfire stories, and this was something that was simply a part of understanding who I was among a long line of hunters and fishermen. The woods and the words were eventually indivisible.

Still: Where was this deer camp? Who were the storytellers you heard around the campfires?

CDW: The deer camp was in Henry County, Georgia, about an hour's drive south of Atlanta. It was a leased camp where we went for several years, but I never saw the actual owner. He was a kind of redneck wizard of oz for me. Everyone told stories, though most anecdotes concerned old hunting trips or tales of mass killings in Vietnam. I remember my uncle was quite proud of telling of how he killed a North Vietnamese Army soldier at Khe Sahn. Like me, he was a Marine. He shot the fellow through the head then collected his helmet as a trophy. Later, one of his ex-wives threw out the helmet when they had an alcoholic spat. He was not too happy about this.

Still: Some critics have compared your writing style/voice to the traditions of storytelling found in the works of Ron Rash, Charles Frazier, Larry Brown, and Cormac McCarthy. Have you, indeed, been influenced by these writers? Who are other writers you admire and why?

CDW: I admire all the writers mentioned. I like the sense of true purpose behind story, the idea of weight. Each of these writers pursues this in different ways but ultimately arrives at the consideration of what it is to be afflicted with consciousness, as Dostoevsky might put it. I would add Jim Harrison and William Gay to this list, as well as Virginia Woolf for her insights into the rendering of deep psychology into a highly realized aesthetic form. Another recent writer who has had a telling effect on me is Paul Harding. His short novel Tinkers is fine stuff.Still: What has it been like for you to have published three books in a little over a year?

CDW: Exhausting. Each of the projects was significantly different from the others. I prefer the more measured approach to the book I’m writing now. It was a good year, but I need more time and space to go in the direction I’d like to with my subsequent work.

Still: Can you tell us about your anthology of contemporary Appalachian short fiction, Degrees of Elevation, and of your collaboration with your co-editor Page Seay?

CDW: I learned that editing was far more of a challenge than I suspected at the outset. Getting a diverse sampling of voices challenges you to read outside of your immediate preferences. In a way, you’re doing a kind of ethnographic work when you’re editing, so you have to be aware of imposing your own prejudices. Having a co-editor helps greatly with that, lends an air of confidence. The dialogic is important to arrive at something more significant for the readership, and possibly the scholarship that might follow.

Page and I are close friends and fishing buddies, but we are also very different personalities in many ways. We drew on these differences of taste and experience to create a collection that I believe is important. We also enjoyed those editorial meetings on the verandah of the Grove Park Inn drinking Bloody Marys, watching a red-tailed hawk hunt the golf course while we discussed the stories.

Still: What kind of research did you conduct to prepare for the writing of your novel Lambs of Men? The story is set in the mountains, but the main character has been a Marine in the Great War.

CDW: The research was fairly typical in that I consulted a few sources about the specifics of uniforms of the time. The Marine Corps history was already part of me, as I served in the late ‘90s, and I recalled details from then. The truth of the mountains was mainly that of experience. Of course, there is the wealth of great Appalachian literature that I’ve read over the years, both fiction and nonfiction.

Still: Elsewhere, you’ve referred to Lambs of Men as “essentially a primitive story.” We’d like for you to elaborate on what that might mean to you as the writer. Why is a “primitive story” important to you as a writer?

CDW: I was interested in a story on a mythic scale, one that borrowed elements from the past in order to reinforce similar concerns of the present. The stripped down elements, the repudiation of convenient technologies, cast the characters into a world on the edge of apocalypse. The woodland became something more deeply psychological and archetypical. I was intrigued by these qualities that seemed to make the story somewhat different than other similar tales of a soldier returned home from war.

Still: We’re struck by the Biblical-like, measured language of this novel. Could you comment on your process in achieving this tone?

CDW: I’m a slow writer, and I’m attuned to the sounds of words as they are written. This calculation seems to result in a King James kind of feeling. I also am continually going back to Shakespeare’s great tragedies for inspiration, so I’m sure this has to have a powerful influence.

Still: Your short story collection, Sinners of Sanction County, was published in 2011. What are some of the challenges you faced in moving from constructing a novel into constructing a collection of short stories?

CDW: Short stories exhaust me nearly as much as novels do, so the biggest challenge was picking up and starting over again each time one was finished. Each story poses its own problems, so if you’re being honest with yourself, you’re scared to death each time that you have absolutely no idea how you’re going to figure the damn thing out. Of course, you’re right. But hopefully you get lucky a few times and it begins to string itself together. I’m glad the collection is out there, but I’m not sure I’m going to be putting together another collection anytime soon.

Still: Can you talk about the relationship your characters have to their landscapes in Sinners?

CDW: This isn’t something I consciously try to write about every time, but several people have pointed this out to me that I do. I guess it’s a reflection of me at the profoundest level. The challenge and solace of water and mountains and desert are simply part of my inheritance. I am fascinated by the construction of the natural world and of the universe that gives it context. If there is a God, it is in the expansive complication of what we fail to comprehend. This metaphor is best realized through the mystery of a walk through the woods.

Still: You’ve talked about being influenced by film directors Terrence Malick and Werner Herzog and their “prolonged gaze into the natural world.” What are some particular films of theirs that readers may be able to connect with your writing?

CDW: Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo are perfectly complimentary to one another, each about a river expedition in South America. Malick’s Days of Heaven remains my favorite, though Tree of Life was amazing as well.

Still: How does teaching enhance or deter your writing?

CDW: Teaching allows me to regularly think about writing and see how it influences others in different ways than it influences me. On good days, it keeps me flexible. On other days, it makes me tired.

Still: What projects are you working toward now? Can you give us any specific details?

CDW: I’m writing a novel called Benediction. It’s contemporary and set in the mountains and involves an old man suffering delusions who lives with his daughter-in-law while his son has been in a federal prison. I look to have a draft completed by this summer.

Read an excerpt from Charles Dodd White’s novel in progress, Benediction

Read Charles short fiction:

Visit Charles’ website