Interview

Interview with Aimee Zaring

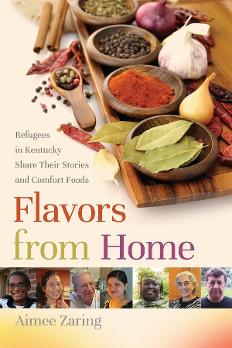

During a potluck at a Louisville school where Aimee Zaring was teaching English to recent refugees, she witnessed her students proudly sharing dishes from their homelands. There she realized the power of food to help bridge cultural divides and got the idea to write Flavors from Home: Refugees in Kentucky Share Their Stories and Comfort Foods.

Each year the United States legally resettles tens of thousands of refugees who have fled their homelands. In Kentucky alone, more than 2,500 refugees are resettled each year, with about seventy percent of them going to metropolitan Louisville, where Zaring was born and raised. In the introduction to the book, Zaring writes: "When refugees prepare their native dishes in their American kitchens, it's like a lifeline to their home countries, a way for them to find solace in an unfamiliar land, retain their customs, reconnect with their personal past and heritage, and preserve a sense of identity. For new refugees in particular, the kitchen is also a place where they can produce a sense of normalcy and stability in an otherwise strange and sometimes scary new world. It is a place where they can serve rather than be served, a place where they can express themselves and exercise some degree of control in a land where they often feel powerless and unheard."

In Flavors From Home, Zaring shares fascinating and moving stories of courage, perseverance, and self-reinvention from Kentucky's resettled refugees. Each chapter features a different person or family and one or more carefully selected recipes. These traditional dishes, with ingredients from their new American pantries, nourish both body and soul and offer an amazing look into the universal language of food. Although it contains recipes, Flavors From Home, is not a cookbook. Instead it is a testament to the determination of the human spirit and the remarkable power of the palate.

Zaring is a graduate of Bellarmine University and the MFA in Creative Writing program at Spalding University. She is the recipient of two artist enrichment grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Her short fiction, essays, book reviews, and interviews have appeared in numerous publications, including Adirondack Review, Arts Across Kentucky, Edible Louisville, The Courier-Journal, and The Rumpus.

Zaring has taught ESOL (English For Students of Other Languages) for over five years through Catholic Charities, Kentucky Refugee Ministries, Jefferson County Public Schools, and Global LT. Being an ambassador of her city and helping immigrants gain confidence and assimilate into their new community through better communication skills is one of her driving passions. Please find out more about Aimee Zaring—and read her wonderful blog—at her website.

Zaring: For many years, I taught ESL (English as a Second Language) in a program specifically designed for elder refugees. At our school we held occasional potlucks where students could share dishes from their homelands. Something magical happened at those potluck dinners. Usually at snack time, the students from each ethnic group would sit together at the same table—but not during potluck days. I was always filled with awe when I looked around the room and saw people from all over the world mingling, coming together around food.

One day it occurred to me that someone should collect all these delicious recipes while they were still close to their original source and before they became altered or “Americanized.” But the original concept of a simple cookbook soon evolved into something much bigger. As I began talking to the refugees about their favorite foods, I was reminded that food is never just food; there are always stories and strong memories associated with it. I realized that leaving out the refugees’ stories would be like leaving out an indispensable ingredient in one of their native dishes.

Still: Have you always has an interest in food writing?

Zaring: No, never. Or at least it was never on my radar to write in that genre, although I’ve always appreciated good food writing. If someone had told me five years ago that I would publish a “cookbook,” I would never have believed it. This was definitely one of those books/projects that chose me first, not the other way around. That’s one of the lessons I learned in writing this book: be open. Don’t be afraid to go outside your comfort zone, even if you don’t think you’re ready or qualified.

Still: Food writing is notoriously hard to pull off properly, but when done correctly—as in your book—it can be a mouth-watering read for the reader. This kind of writing really allows a writer to be sensory, doesn't it? But what is particularly hard about it?

Zaring: I appreciate the compliment because as I mentioned, I had never had any experience with writing about food prior to this book.

People sometimes ask me why I think food writing is so popular, and I think it’s for the exact reason you mention—it’s such a sensory experience, both for the writer and reader. But for me, since I had never identified as a food writer before, the writing didn’t come naturally, at least not at first. I started off trying too hard to show off my food writing chops, so to speak—perhaps to prove to the reader and myself that I could pull this off. But after a while, I just settled into the writing and the stories and tried to write as honestly as possible. In that respect, good food writing is no different than any other good writing. I think that writing about food in particular has improved my writing overall, simply because you do have to be so sensory and descriptive, and in my case, I had to be even more so since I was writing about ingredients and foods that I knew many American-born readers would be unfamiliar with.

Still: The book focuses in particular on refugees. Not everyone may realize that the word "refugee" denotes that these are people who have fled their homeland because of violence, warfare, or persecution and are legally resettled in the United States. What are some of the experiences the refugees in the book have escaped?

Zaring: Nearly all the refugees I interviewed for Flavors from Home were driven out by the trickle-down upheaval and chaos resulting from war, military dictatorships, or political uprisings. The first refugee featured in the book came to America as a young girl with her family after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Several refugees in the book are from Myanmar (Burma) and were persecuted for their religious and/or political beliefs by the country’s longstanding military junta. Two refugees in the book are from Bhutan, the country often referred to as “the happiest in the world,” yet their specific ethnic group (comprised mainly of Hindus) made them a target in the small Buddhist-dominated kingdom. The last chapter in the book features one of my former students, a political activist who spent over two decades of his life in jails because of his enduring fight to defend human rights. There are 23 stories in the book, but these examples represent some common types of circumstances that deliver refugees daily to the U.S.

Still: While providing wonderful recipes and touching stories, the book also offers important history lessons about the refugee experience, the histories of several different countries, even deep looks at spices and other ingredients. You must have done an enormous amount of research.

Zaring: Yes, and to tell you the truth, this was part of the reason why I originally shied away from this project, because I recognized just how much work it was going to entail. The workload became even more involved when my publisher wanted to see more sidebars (about ingredients and other cultural topics). The sidebars were very time-consuming to write, due to the amount of research each took, but I do think they provide an extra layer of supplementary information that otherwise would have felt forced in the stories or recipe introductions.

As to the historical information, I had to be careful how I presented that material. I wanted this book to focus on what unites us rather than what divides us, but wherever appropriate, I tried to give a historical backdrop of a country’s conflict, especially if it was important to the understanding or emphasis of a refugee’s story.

I met a woman the other day who said she’d learned more in reading the two Bhutanese stories in my book than hours of research online about the Bhutanese conflict. That was wonderful to hear because that was one of my goals, to put down in the simplest of terms very complex events and situations and to at least give people a glimpse into what happened, and is happening, in these countries. Many people don’t have the time or energy to learn more about our new immigrant neighbors, even though they might be very interested in them. I’m glad I’ve been able to pass along a little of what I’ve learned over the years in working with immigrants and doing research for the book.

As a writer I’ve always known how powerful words are, but in teaching ESL, I’ve also seen how limiting language is . . . . much can be communicated without words, through the simple act of sharing a meal together.

Still: One thing the book does so beautifully is show food as a universal experience, as a way that we are all connected. How did you realize that in a bigger way while working on this book

Zaring: This was the thesis I started out with before writing the book. But it actually took writing the book and visiting the kitchens of these refugees for me to see the theory borne out.

One of my favorite memories during the writing of the book illustrates this well I think. I was visiting with a Burmese couple. The husband, who had good English skills, had to leave early, leaving me alone to cook and eat with his wife, who knew very little English. But even though we barely spoke during our several hours in the kitchen together, even though she is a mother and I’m not and we both come from different countries and backgrounds, I left there feeling like we had really bonded over our shared food experience. She could tell by my oohs and ahhhs how much I appreciated the food she’d prepared for me, and she was able to communicate so much by the attention and care she put into the meal and by showing me step by step how to prepare her dish. As a writer I’ve always known how powerful words are, but in teaching ESL, I’ve also seen how limiting language is too. This experience was a great example of how much can be communicated without words, through the simple act of sharing a meal together.

Still: The very first chapter in your book recounts the experience of a Hungarian woman who relocated to Appalachian Eastern Kentucky in the late 1950s, which is one reason we wanted to interview you and feature your book. What has been your own experiences with the region

Zaring: It’s funny you should ask this because just the other day I had a business meeting with someone I’d never met before. He turned out to be from Appalachia, and I felt like I was sitting down having coffee with a dear friend from Appalachia. In other words, I felt instantly at home. What I find so refreshing about people from Appalachia is how genuine and straightforward they are. They tell it like it is, but in such a way that never seems rude or disrespectful. I really admire this quality. They also seem to have a deep love and connection to their land, which shapes who they are and how they live. And they are almost always natural-born storytellers. I’m grateful that I have some close friends from Appalachia. Just hanging around with them has given me a little window into their microculture and a broader view of people from that area.

Still: On that same note, what has been your food experience with Appalachia?

Zaring: I grew up without having a garden in my backyard; canning was a foreign concept. So I have an appreciation for how homegrown, fresh, and made-from-scratch Appalachian food generally is. Even though Louisville is only a short drive to most Appalachian towns, sometimes it seems like our foodways are worlds apart. Even though spoonbread, for example, is considered a Southern dish, I’d never had it before last year in Berea.

Still: You prepared every recipe that's in the book. Tell us about that. Were there any mishaps? And what was the tastiest dish?

Zaring: Oh, were there ever some mishaps! One of the most challenging recipes for me to duplicate was the African dish “fufu.” It’s the equivalent of the staple dishes of rice or bread in other countries and reminds me of gummy mashed potatoes. The fact that I had trouble with it is rather embarrassing considering it should take only about ten minutes to cook and has only two ingredients—one of them being water! But because of language barriers with the cook, I wasn’t using the correct flour at first, and the dish will form lumps in a heartbeat if you don’t stir it just right. There really is an art to it, and I love how effortless Sarah Mbombo, the cook from The Democratic Republic of the Congo, makes it look.

Other dishes are memorable because I find myself craving them as my own adopted comfort foods. The Bhutanese national dish “ema datshi” is one example. It’s not only easy to make but I love the combination of cheese, hot chili peppers, vegetables, and cumin. I can almost smell and taste it every time I write or talk about it. That’s an example right there of how powerful and evocative food memories are.

Still: The recipes in the book are absolutely wonderful but some of them require somewhat exotic ingredients. More than one person in the book says they get some of their ingredients—particularly spices—online. Have you bought spices and other ingredients online? If not, what are some other ways to procure ingredients that may not be at your local grocery store?

Zaring: I didn’t have to buy any spices online for writing the book, and it was surprising to me that rarely did I hear a refugee complain about having trouble finding ingredients. Even in smaller towns like Owensboro, ethnic groceries can be found. And many Asian and Indian markets, which are more common these days, carry other countries’ native ingredients, so you don’t have to find, for example, a “Bhutanese” or “Burmese” market. Even some organic stores like Whole Foods carry many of the ingredients mentioned in the book.

Another way refugees procure their native ingredients is by growing them themselves. Several have their own gardens where they grow produce from their homelands, provided the crop is compatible with the climate and growing conditions here. Refugees are some of the most resourceful people you’ll ever meet. Where there’s a will, there’s a way, and their will is very strong to eat their native foods here in America.

Still: If you were a refugee forced out of your life in the United States and resettled in another country, what would be the meal you'd make that would carry you back home via your tastebuds?

Zaring: Since I have German ancestry on both sides of my family, I have to say that my Mom’s German potato salad is one of those recipes that feels like home to me. It’s actually my paternal grandmother’s recipe and is about as authentic as it gets. And I love just about anything with bacon and cheese in it.

Speaking of bacon and cheese, I’m also really fond of breakfast foods: bacon and eggs, cheese grits, biscuits and homemade jelly, hashbrown potatoes, waffles and pancakes—you name it. I think if I were away from home and couldn’t experience a good down-home Southern breakfast once every week or so, I’d have some major withdrawals. And I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t fare very well without some good bourbon and chocolate.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Contest Masthead Submit Feedback

_____________________________________________