The Fall by Robert Cumming

v.11aI am free, I think,watchman of the worldwith only the dark to see by.. . . .But freedom is nevera weightless thing, but clarityin what we bear, how fullwe put our shoulder to it.

−Joseph EnzweilerFrom A Curb in Eden

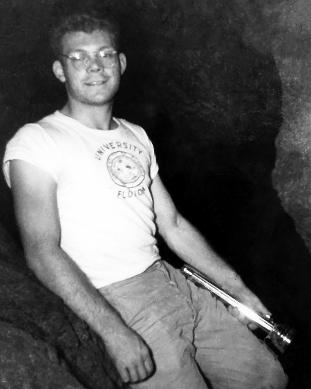

May 14, 1949, was a bright sunny Saturday in Gainesville, Florida, and now as I write this more than 70 years later, I remember that day as if it were yesterday. I had, just the day before, finished classes for my second semester at the University of Florida, and about a week remained before the final exams were to start. I was anxious to leave the books behind and, at least for a while, get out into the field and visit some of central Florida’s wilderness areas. At that time, I had years of experience in exploring wild places throughout the United States, but I had never entered a wild cave. At the University, we had heard a lot of talk of the legendary Warren Cave, which is located about 14 miles from the university campus. I knew that it had a colorful history and great biological interest, but I had never met anyone who had actually been there. So on that day, I decided to go.

Warren Cave is the longest dry cave currently known in the State of Florida, with about four miles of passageways mapped. It is located in a wooded area known as the San Felasco Hammock, and in the mid-20th century, it was on private property with no restrictions on entry. In 1949 the cave was only reachable over rough unpaved country roads. When I first visited the cave, it had been a popular site for over a hundred years, and a lot of local legends had built up around it. During the early 19th century, the territory that later became the state of Florida was embroiled in the Seminole Wars. On September 11, 1836, nine years before Florida became the 27th state of the union, Colonel John Warren led his men against a band of feisty Cherokees in the “Battle of San Felasco Hammock” near the site of Warren Cave. Legend has it that Colonel Warren discovered the cave and entered it, but this cannot be verified. It is apparent that he agreed to have his name attached to the cave. Warren Cave came to be better known through north-central Florida when the US Geological Survey included it on a map of the area in 1894, but it has always been familiar to local residents, whatever the color of their skin.

I was accompanied that day by Mark Adrian Dixon. As freshmen at Florida, we had worked together in the Registrar’s Office and become good friends. Mark, then 18, was an intense, tall, skinny, young man (about 6’4” and 118 lb.) from Fort Lauderdale. His mother was dead, and through high school, he had lived with his ailing and elderly father, who was retired on a small income. Mark had an academic scholarship, but it only paid tuition. At the University, computers were beginning to replace the hand-written records that had been standard until that time, and we became quite familiar with mountains of punched cards. Our card shuffling salary was $33.00 per month, and Mark lived on that, being very experienced and inventive in providing life’s necessities for little money. Mark was interested in Geology, and we loved to go out into the field together and explore. With much effort, we had visited many interesting places near Gainesville on our fat-tired single speed bicycles of that era. Mark’s bike was a simple basic machine with no fenders. It had a very high seat post which placed his long willowy torso above the window level of cars that he passed so that all that was visible from inside were his long skinny legs driving the bike down the road 30 feet with each powerful stroke. At Christmas time in 1948, Mark had visited our family in south Jacksonville, riding his bicycle the 80-mile-distance each way from Gainesville over the narrow, congested pre-interstate highways of the day. Mark turned out to be a resourceful and dependable friend.

We packed some snacks and studied our maps. The scenes of that day are vivid, and I can still smell the fresh air and see the scattered clouds as we climbed onto our bicycles and, keeping to the back roads, headed out from the university campus into the countryside. It would not be a comfortable ride. It took us over an hour to get to the site. With our primitive bicycles riding the rough sandy surface, it was hard work, but we arrived at the cave entrance late that morning.

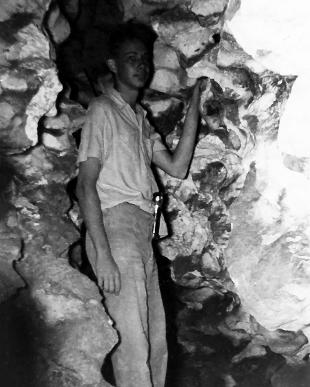

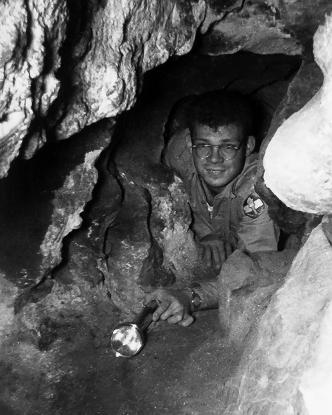

In 1949 the cave entrance was about a quarter-mile from the unpaved road which passed nearest the site. We rolled our bicycles along the path to the cave, parked them, turned on our flashlights, and descended into the small sinkhole leading to the entrance. The passage took us back about 30 feet to the first drop-off, about 20 feet down to a ledge, and then a short distance to another 25-foot drop-off and the lower level of the cave. This part of the cave was known as the “pit,” a narrow passage with a very high ceiling and near the water table. Nine years earlier, a new species of blind cave-adapted crayfish, Procambarus palladus, had been discovered here and described by Horton Hobbs, then the world’s leading expert on Florida freshwater crustacea. As we moved farther into the cave, the passage gradually led upward, and we climbed about 50 feet until we eventually reached the level of the entry passage. From this point, we moved back into branching passageways and explored those back areas of the cave that were easily accessible at the time.

I planned to work my way along the upper level of the cave using the many handholds in the rough limestone walls. When I got over the deepest part of the cave, I reached out to grab a solid-looking limestone nodule, and as I put my weight on it, the solid stone crumbled into dust.

Returning to the entrance, Mark retraced our route in, patiently climbing down into the pit and up on the other end to the exit. But I decided that it was a waste of effort to descend into that deep hole only to climb out again. So I planned to work my way along the upper level of the cave using the many handholds in the rough limestone walls. When I got over the deepest part of the cave, I reached out to grab a solid-looking limestone nodule, and as I put my weight on it, the solid stone crumbled into dust. I saw my flashlight cascade into the void, and as it disappeared, I too came loose from my perch. What I remember of that long descent through the total darkness was being bounced around by the cave walls, and the frequent bright flashes of light as my head hit the limestone.

The fall was about 50 feet vertically, but not straight down since the cave walls were angled slightly from one side to the other. These many years later, I still remember what a long time it seemed to take to fall such a short distance as if time slowed down. At the bottom, I crunched into a tight crevasse, and I just lay there in the darkness, unable to move, wondering what to do next. I never entirely lost consciousness, and I slowly regained some awareness of where I was. Mark had heard my fall, and after a while, he made it down to where I was lodged with a spare rope. He tied the rope around my torso, and between the two of us, pushing, pulling, and wiggling, I struggled free, and after an arduous climb, we finally emerged from the cave. At that point, I began to realize that we were a long way from home.

After leaving the cave, we slowly returned the quarter-mile to the road. I was limping badly, using the bicycle as sort of a moving crutch or walker. My right leg was severely swollen and not functioning well, and my orange University of Florida T-shirt was drenched with blood. I was still quite dizzy and certainly could not ride the bicycle. It was also clear that the long hike back to civilization was out of the question. So we sat down by the road to think things through.

After a while, we heard the rumble of a vehicle approaching. A Model-A Ford pickup lumbered toward us, and as we sat there in a daze, moved on past. About 100 yards down the road, the truck stopped and started to back up. The ancient vehicle stopped right in front of us, and an old farmer in the driver’s seat asked if we needed any help. Mark said that we sure could use a lift into town. The farmer’s wife, who had been in the passenger seat, moved into the back of the truck with their three daughters, and we added two bicycles to the crowded bed. Mark and I crammed into the cab with my bloodied right arm hanging out the window. The farmer was on his way to visit his son at another farm nearby, and that’s where we went. The son loaded us into a more modern truck and took us to the University of Florida Infirmary, where I spent the following week.

The medical examination showed many injuries. My right leg and right arm were somewhat mangled and bloody with many deep bruises, but though they were relatively useless, no bones of my arms or legs were broken. I had lost a lot of skin and considerable blood. X-rays showed multiple deep fractures in the nose and a cracked maxilla but no other fractures in my otherwise battered skull. I had suffered at least one significant concussion, not much to worry about, but certainly an inconvenience. I joked that I was probably saved by having all of the energy of the fall absorbed by my head, perhaps, I thought at the time, the least functional part of my anatomy. It took a while to get all of the wounds cleaned up, and they started to give me massive daily doses of penicillin to prevent infection in the deeply damaged areas of my nose and face. Since my parents were already out of the country and it was between semesters, there were few visitors. I had a lot of time to read, study, and reflect.

When I was released from the hospital, I immediately took the final exams that were still scheduled and passed them without difficulty. The three exams I missed were deferred to the summer session. But the story of that fateful visit to Warren Cave was far from over. A few days after my release from the hospital, while I was still recovering from the head and leg injuries and trying to learn to get about with crutches, I became intensely ill and was rushed back to the University Infirmary. I had a life-threatening allergic reaction to the enormous doses of penicillin I had been given during my first stay. I spent another week in the hospital, with ample time to think about what had happened and put the events of May, 1949 in perspective. I took the three final exams that I had missed during the summer session receiving two “A”s and a “B.”

As I look back on the incident at Warren Cave now, from the vantage point of over six decades later, what interests me most is the nature of those memories, their clarity, and detail, the absolute “hyper-reality” of those events, like high definition video. In this respect, the memory of the accident at Warren cave is different from other deep memories of events of long ago, more focused, less fuzzy. My memory of the Warren Cave event is similar to memories described by Eric Kandel, a memory researcher who received the Nobel Prize in 2000. In his 2006 book, In Search of Memory. Kandel describes scenes from his childhood in Vienna in the late 1930s as the Nazi campaign to eliminate the Jews was taking hold. His memories of those years, barely escaping the concentration camps, like mine of Warren Cave, are vivid and detailed after more than sixty years. In both cases, these are memories of events that were at the time unusually traumatic, and which had a significant impact on the subsequent course of our lives. They are memories of unanticipated occurrences that generated intense focus and attention over an extended period and that were revisited in recall periodically over many years. They fit in and contribute to life narratives that we each construct, and since they are often recalled, they are perhaps edited and refreshed along the way to better support those stories.

The cave had received my attention, but as I lay in that hospital bed, I refused to be defeated by a hole in the ground. I realized that what happened on that day at the cave had been my fault for not being adequately prepared for a visit to this remarkably beautiful and unique place. I did not know it at the time, but there were at least two credible accounts of fatalities of nineteenth-century explorers falling while attempting to bypass the pit on the way out of Warren Cave. I resolved to be more careful in the future to better plan and equip future excursions. I started visiting Warren Cave and other Florida caves regularly, and though I witnessed several severe accidents over the next 20 years involving others, I never had another accident in cave exploration myself.

As far back as I can remember, even as a toddler, I have felt an intense attraction to the natural world and to the living creatures that populate it. I inherited the use of my father’s microscope when I was in elementary school and spent hours looking at insect wings and tiny pond creatures. There were often cages in the yard, temporary homes of denizens of the nearby woods, and bags of snakes under the bed, but that was just who I was; I never considered it unusual. At the time of the Warren Cave incident in 1949, a subtle change in my attitude began to develop. The natural world was no longer just a hobby or a pastime, but a deeply serious thing, and I started to understand that it would become a significant organizing theme for the rest of my life. Cave exploration became a part of this theme because I knew that extreme environments, such as caves, provide a clear, and often disturbing, view of the fragile and complex web of life on this planet and the way living things adjust or fail to adapt, to the challenges in their surroundings.

As I started to explore caves frequently, a small group of other nature addicts joined me, and that group evolved into the Florida Speleological Society, a Grotto of the National Speleological Society, and the current custodian of The Warren Cave Nature Preserve. I served as its first president. I continued to explore wild caves as a part of the beauty and complexity of nature for many years throughout the eastern United States and in several other countries. But I was also involved in field biology in many different environments and with increasing intensity. A year after the Warren Cave incident, I had my first significant experience of collecting in the tropical rain forests in Panama, and I became very active in seeking out mentors among well-known field biologists and ecologists of the day.

Cave exploration has taught me much about the beauty and fragility of wild places and their importance to human wellbeing. And it all started with an apparent misadventure, which turned out to be not so bad after all.

photos supplied by the author

return to creative nonfiction home