Trampoline

A Novel in five acts by

Robert Gipe

. . . OUR STORY SO FAR

Our narrator, Dawn Jewell, is fifteen and lives with her grandmother Cora in the coalfields of east Kentucky. Dawn’s daddy is dead and her mother pilled up. Cora leads a group of locals trying to block a strip mine permit on Blue Bear Mountain, Cora’s ancestral home. Along the way, the dog of one of Cora’s group is poisoned. At the end of Part One, Dawn, who wants only her driver's license, to be left alone, and perhaps to meet the disc jockey Willett Bilson, jumps up at a permit hearing and defends Cora when her right to protest is challenged. Dawn is mortified to have done something so public.

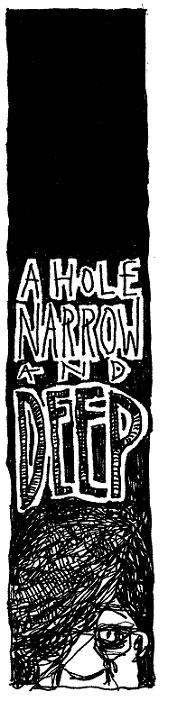

Escape Velocity

Part Two: Smother

When we were walking out of the hearing, a bald man in a hoodie and long shorts came up to me and said, “That was awesome.” His face was right up in my face. His eyes swirled in his head like two Sasquatches penned up in a dog lot. I don’t know where he was from, but it wasn’t here. “You are one awesome chick,” he said, stabbing his meat cigar finger right at me.

He had canvas bags hung over both shoulders. “Can I do a quick interview?” he said. “Just a quick one.”

A miner’s kid bumped into me and the bald man took me by the shoulder.

“I’m with a radio station. Bilson Radio. I don’t know if you ever heard of it.” His voice seemed to come from his crazy Sasquatch eyes.

“Mamaw listens to it all the time,” I said.

“OK, OK. All right,” he said, his head bobbing. “Is that you,” he asked sticking out a hand for Mamaw to shake.

“I’m Kenny Bilson.”

“Yes, that’s me,” Mamaw said.

“Now what is your name?” he said to Mamaw. She told him and he said, “Oh wow. Yes. You call my uncle’s show all the time. Yeah,” he said, bobbing his head, “I know yall. Yeah. Hey. Let me do an interview with yall. About this here tonight. Cause you and what you said. Yeah. It was right. Cataclysmic. Our listeners need to hear it. Yeah. And you ma’am”—he pointed again at Mamaw—“they told me that I had to talk to you. That you are the main one”—people were starting to look back at us as they walked past—“the straw that stirs the drink for real.”

Mamaw said, “It’s getting late. I need to get this youngun home.”

“Oh yeah, me too. Me too. I got the baby. Yeah.” He thumbed back over his head. A baby in a black onesie sat in a carrier on a folding table two women were standing wanting to take down.

He took us in a little room off the big room. Dented folding chairs were stacked against a junk popcorn machine. There were broken lighting fixtures and moldy ceiling tiles piled everywhere. He set the baby down beside him in a folding chair with a bent leg. He got out a tape recorder, a microphone, a tangled cord and hooked them up. He put a cassette with no label in the recorder and asked us to tell him what happened, tell him how we felt about it, what we hoped would happen. He draped his arm across the baby carrier.

“Oh yeah, that’s good. That’s good,” he said as I spoke. Mostly he said nothing, just sat smiling while we talked, like we were saying what he wanted us to say. When he finished, he closed up his recorder, tucked it back in his canvas bag.

“Yeah, we’ll put you right on the radio. Hell yeah. Sorry ma’am, but yeah. They’s a little dude on the mountain he is so going to dig this, he’s the one who edits all this stuff. My little brother. Willett. Yeah, you got to listen to it.”

We walked out into the parking lot.

“Probably be around seven minutes, unh-hunh. Yeah. Have yall had supper? They say that dairy bar there has badass shakes, yeah.”

“We had supper.”

“OK. Yeah. But Dawn, man, you are awesome. Cataclysmic. Yeah. We’ll call you when the show is gonna be on.”

The baby started to stir. Bald Sasquatch Kenny waved a pirate rattle in the baby’s face.

“Well,” Mamaw said, “it was real nice meeting you.”

Kenny said, “Yeah,” and popped the hatch on his dented no-front-bumper Subaru. He put his equipment in. “Yeah. So do yall think you’ll hear anything before Christmas?” He closed the hatchback.

“Honey, you don’t want to leave that baby back there, do you?”

“SHIT! No. No. Yeah. Thank you all.” Kenny opened the hatch and took the baby out. “OK. Well. Bye now.”

Mamaw was in the car. She rolled down the window. “Dawn honey, do you want to drive?”

“Goodbye,” Kenny said. “Great. Great to meet you. Yeah. Great.”

I nodded. Kenny kept standing there. I got in the Escort. I sat there with my hands in my lap.

“Let’s go sweetheart,” Mamaw said.

I started the car. We left the meeting.

“Them state people are just going through the motions,” Mamaw said as we crossed the bridge at the mouth of Blue Bear Creek. “They know what their job is. They have their orders, and they don’t come from us.” Mamaw faced me as she spoke. Her eyes glittered like stones in a stream. “You got to change their orders. You got to change the people telling them what to do. You got to make those people feel the pinch.” I liked to see Mamaw’s eyes glitter, but I didn’t know how she was going to do what she was talking about.

“Who gives the orders, Mamaw?”

“Really? The companies. But the governor,” Mamaw said. “He can do some.”

Mamaw twirled a toothpick on her tongue.

“About what you said up there.”

“I don’t guess I should have called that woman a heifer.”

“No. Probably not.”

“But she is.”

“I don’t like meetings,” Mamaw said. “They just tear people apart. Our fight aint with nobody who lives here.”

That didn’t make sense to me and I told Mamaw so.

Mamaw bit down on the toothpick over and over. “They’re being put up to it,” she said.

We drove the rest of the way home without talking. Snowflakes twisted in the headlights.

That night I lay awake a long time. I thought about people who patted me on the back as I came out of the meeting. I thought I would get my ass whipped before I got to the car, but I didn’t. I felt like Evie said it did when you got baptized.

Mamaw was stacking something in the kitchen. I heard the clink clink clink from my narrow bed in the front bedroom. It sounded like she was sorting bullets, shells, some kind of ammunition. Ghosts in bedsheets ran bulldozers through my dreams. I woke Wednesday morning wishing I could turn on the radio and hear my voice come out of it. I could smell the coffee maker spit out Mamaw’s thin coffee. I got up.

≈

I walked out to the end of the ridge road to catch the school bus. The bus came up the back side of the mountain against a skim-milk sky. The bus was full of little kids,

They were afraid of spit in their ears, gum in their hair, knuckles to the base of their skulls. The bus stank of middle school b.o. and cooking grease. I sat down next to a little boy who wiped his nose with an infected finger. Hardly any of the kids who rode the bus had parents working at the coal mines. The ride was quiet.

When I got off the bus, Evie grabbed my arm and headed me out into the parking lot towards her car. “Did you say something at that meeting last night?”

“Yeah, I said something.”

“Why?”

“Cause they talked bad about Mamaw.”

Evie stood looking at me over the hood of her tan Cavalier.

“You don’t think your mamaw can take care of herself?”

“I guess.”

“You don’t think she knows what’s she’s getting into?”

“Shut up Evie. You’re retarded.”

Evie got in the car. So did I.

“You’re the one who’s retarded,” she said.

I fooled with everything loose in that car. The lighter. The black rubber butterfly hanging from the rear view. The Missy Elliott air freshener. I was scared but wouldn’t tell Evie. I wiped my eyes.

“We need to go,” Evie said. “Get out of here.”

“I have a French test.”

“God Almighty,” Evie said. “Yall have a test in there everyday.”

I opened the car door.

“Don’t, Dawn.”

“Aint nothing gonna happen,” I said, not really believing.

“When’s your test?”

“Second period.”

“Don’t go in til second period.”

“You stay with me, Evie.”

“I caint. Donnie’s got a court date.”

“What time?”

“Right now.” Evie said. “You should just take a zero on that test.”

A bell played over the loudspeakers. I got out of the car and started walking towards school. Evie’s horn honked. She waved me towards her. I went to her window.

“You want a beer?”

I shook my head.

“You want a Xanax?”

“No.”

She got a pint bottle out from under the seat. I drank an orange capful.

“Hope it comes out OK with Donnie,” I said.

“It won’t.”

When I turned at the door of the school, Evie was still sitting there. I walked through the lobby and buzzed to be let in. My first period class was at the far end of the building on the third floor, the longest possible walk. Two nerdy girls passed me on the steps, looking at a clothes catalog. The hallway to my history class was two hundred yards long. At every window in every door people rolled their eyes, lay with their heads on their desks, leaned into one another, threw punches into arms, tossed paper wads. Teachers peeped out doors as they spoke.

Everyone that could, in cell after cell, looked up to see what was passing. A door opened in front of me. My brother Albert stepped out into the hall. He lived with my uncle Hubert, and I never saw him, especially not at school. He was a senior and only came to school to sell pot. He had a hall pass anybody who looked would see was fake.

“What are you doing here?” I said.

“What are you doing here?” he said.

“I go to school here, douchebag,” I said.

Albert grabbed hold of my shirt sleeve. “Momma wants you to come stay with us.”

“Don’t talk to me about Momma, Albert.”

Albert grabbed hold of me again. Tighter. A year before I could whip him. Wasn’t so sure I still could that day.

“You need somebody,” he said, “to talk some sense into you.”

“Who? You?”

Albert’s rat eyes burrowed into me. I was the target of his arrowhead nose. He said,

I jerked away from Albert. I could see people in classes gathering up their stuff. The bell was about to ring.

Albert reached his left hand out to touch my cheek. I busted him in the face just as hard as I could. I meant to knock his eye clean out of his head. He staggered but didn’t fall. Faces gathered at the narrow slits of glass in the classroom doors. Albert put his hand over his hit eye and stared at me with the other.

“You think Daddy would want you talking at them meetings?” Albert said. “He’s spinning in his grave.”

The bell rang and I stuck the crown of my head right in Albert’s mouth with everything I had. He went down, flat on his back. I started stomping him. He grabbed my foot and I fell, but I landed on my knees right on his chest.

I beat him in the face with the spine of my French book, wishing it was hardback. He caught me by the hair, pulling hard, when two teachers got me under the arms and pulled him off of me.

The school suspended me. Momma took Albert to the hospital and Mamaw took me home. That night I lay in bed, grinding my teeth, swearing at the ceiling. I couldn’t get my breath.

Mamaw got up real early Thanksgiving morning. There were three pie crusts in tin pans lined up on the counter by the time I got up. We were going to her brother Fred’s house for Thanksgiving dinner on Drop Creek and she was making chess pies. Mamaw moved like she was mad, everything short, sharp, and hard. Only thing she said was, “Store lard caint touch what we got ourselves.”

We were supposed to be at Uncle Fred’s at twelve but Mamaw took her time and it was almost twelve before we left the house. Mamaw’s sister Verna and her buckeye husband were in the car in front of us as we headed up Drop Creek. It was gray and dreary when we got out of the car at Fred’s house. Verna hit her husband on back of the arm and asked did he bring the playing cards. He said he did.

We walked up the broad steps onto Fred’s deep dark front porch. My cousin Kevin’s little boys were shooting paintball at a target at the side of the house. The targets were stuck on Uncle Fred’s woodpile, the biggest wood pile I ever seen.

When we walked in the front room of the house, all four of Mamaw’s nephews were standing there in front of the television.

They looked at us like they’d been waiting, but they didn’t say anything. Two were Fred’s sons. The other two were Verna’s. Verna lived in Cincinnati but the boys stayed in Canard County. Mamaw’s nephews all worked on strip jobs around Blue Bear or wherever they could get work. Uncle Fred’s younger son Denny worked on the strip job Mamaw’s petition was about.

We carried pies in the kitchen. Uncle Fred’s wife Genevieve took them from us. Genevieve was round and nice, but whenever we went over there she said at least once what a pretty girl I could be if I wouldn’t wear Halloween makeup all over my face.

“Dawn, you been sick?” Genevieve said as she took my pie.

One of my eighth grade cousins, a boy with a football jersey on, ran through. “She got suspended.”

“Is that right?”

“Don’t matter. We’re on break anyway,” I said.

Fred laughed at that.

Genevieve sat us down to eat at a round table off the kitchen. The dishes were white with flowers on them. Fred passed me a pan of rolls. Aunt Verna was filling a water pitcher at the sink when a hose came loose under the sink and water started flooding out all over the kitchen floor. Fred moved quickly, quietly, and turned it off. He was soaked. He smiled.

"Drownded," was all he said.

Genevieve left the kitchen and returned carrying a folded shirt, plaid and soft, a clean white v-neck t-shirt. Fred patted me on the shoulder as he passed behind on the way to the back of the house to change his clothes. Genevieve had the water on the floor mopped up before the bread got cold. Fred came back. He had a tan canvas coat on. He nodded at his wife and left.

“He is going to check on the mine,” she said. “They have a new boy working the guard shack.” We finished eating and cleared the dishes and pans from the table. Genevieve set a pound cake, a stack cake, a plate of cookies, and one of Mamaw’s chess pies out on the table.

“Should we wait for him to get back?” Mamaw said.

“He’ll be a while,” Genevieve said. “Untelling.” She stacked plates, piled silverware. I looked at Mamaw. She nodded at me. I rose to help.

“I’m fine, Dawn,” Genevieve said, “Why don’t you go out there and see what Denny’s doing.”

My cousin Denny sat in the living room slouched down in an arm chair. A deer head hung above his head. He wasn’t paying attention to the football game on the tv. He smiled at me and got up and went in the kitchen.

Denny brought me a Mountain Dew and sat back down in his daddy’s chair. His mother passed through, got a big piece of Tupperware out of a closet. She went back in the kitchen and brought me a paper napkin. I had a headache. My skull felt like it was about to split in half.

“Denny,” his mother said, “You get in some wood. Start a fire.”

Denny lifted up out of the chair.

“Come on,” he said. I didn’t move. He tapped me on the side of the knee. “Come on.”

We went out to the big woodpile. I stood waiting for Denny to pile my arms full of wood. He turned around and took a pint bottle of whiskey out of his jacket pocket.

“Where’s your pop?” he said.

“In there.”

He poured some of the whiskey in his red plastic cup. He handed it to me. I took a sip and was glad for it. One sip and the world widened out in my head.

I shook my head. It was enough. He took a sip.

Denny filled my arms with split oak. He waved me in the house and even though the woodpile was big as a trailer, he split more, long arching strokes with the ax. We went in the side door. There was a mud room, where their boots and workclothes stayed. I seen broken glass sitting on a Styrofoam tray like meat comes on at the grocery store.

“He making you pack that wood?” Fred was behind me. His eyes looked tired too. He took the wood from me and stacked it by the stove.

Everybody was sitting in the TV room when we went back in the house. One of the grandkids was in Fred’s chair. The grandkid got up and Fred sat down. Mamaw and the other women came in and stood around behind the chairs and sofas.

Fred looked up at Mamaw. “How you getting along with the tree huggers, Cora?”“Doing all right,” Mamaw said.

“Well, I’m worried about you.”

“Who’s winning the football game?” Genevieve said.

“And I have to wonder what you’re thinking getting that youngun mixed up in it.” Fred said.

Nobody said anything. All those big men made me smother. I went out in the yard. There were six four-wheelers parked on the gravel. I took off on one.

The tires crunched against the frosted ground. The bark of the motor ran through the skeleton trees. I wound straight up hill, dipped across a dry creek bed and then up again. I came to the edge of the woods, to the mine the meeting on Tuesday night had been about. I turned the four-wheeler engine off. The strip job was quiet. A hawk circled far out above the grass on the reclaimed section. A security man came out of the guard shack into the sun. He sat down on a block of wood. He ate out of a plastic container, sopped Genevieve’s yellow gravy with a dinner roll. The sun made long blue treetrunk shadows, turning the stones at the edge of the highwall gold and orange. The light anyway was beautiful.

I walked away from the four-wheeler.

You walk on and on, thinking you’re going deeper into the woods, deeper into the past, farther away from the bullshit of the world and then you trip over the cable running from somebody’s satellite dish and then you see the trailer and hear the creak of the trampoline springs and then it’s oh well, welcome back. I wished I was warm, by the stove at Mamaw’s, cutting pictures out of magazines looking at winter through her dripping windows.

I walked the rutted mine road back towards the house. An owl swiveled its head high up in a poplar tree. Its doubloon eyes fixed on me. It flapped to another tree, deeper in the woods. I followed it. The owl moved to a third tree. I went after it, my eye fixed on the owl, and the ground beneath my feet broke in on itself, made a hole narrow and deep.

Once I was in, it felt like the ground closed up over me. It didn’t; I could still see the sky, but the hole was deeper than I was tall. I tried to stand, but my ankle gave out on me, and when I fell I peeled back the skin over my shinbone on a wedge of sandstone. My pants leg bloodied up, and I rolled over on my back at the bottom of the hole.

≈

Author's Statement:

I was born in North Carolina in 1963 and was raised in Kingsport, Tennessee, a child of the Tennessee Eastman Company, Pals Sudden Service, and the voice of the Vols, John Ward. My dad was a warehouse supervisor and my mom a registered nurse. I went to college at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina where I was a DJ for a student radio station I helped start. I went to graduate school at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and got a masters in American Studies. I worked as a pickle packer, a forklift driver, and eventually landed a job as marketing and educational services director for Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky in 1989. At Appalshop I worked with public schoolteachers on arts and education projects. I met my wife, Robin Lambert, at a conference in 1992, and we bonded over an interest in rural communities and an opposition to school consolidation. We married in 1993. She is my heart's delight. Since 1997, I have been the director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland, Kentucky. I am one of the producers of Higher Ground, a series of community musical dramas based on oral histories and grounded in discussion of local issues. I am also a faculty coordinator of the Crawdad student arts series. I have had fiction published in Appalachian Heritage and have attended the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman every year since 2006.

I have been working on the characters in Trampoline since 2006. The narrator is Dawn Jewell. She lives in a coalfield county in eastern Kentucky, and is in high school when Escape Velocity takes place. She's having a rough go of it. The sound of people telling one another stories is the most precious sound in the world. Trying to catch that sound on the page is my favorite part of writing. Most of my favorite writing—Flannery O'Connor's stories, the novels of Richard Price and Charles Portis—seems to me written by ear. When writing is going best for me, it's like taking dictation from voices I hear in my head. As far as the drawings go, I have drawn pictures all my life, much longer than I have written stories, and with more compulsion. Escape Velocity is the first time I have seriously tried to integrate fiction and drawing. I love episodic storytelling, especially the great HBO series—The Wire, Six Feet Under, Deadwood, etc.—and have enjoyed thinking about how to break a story into semi-coherent pieces.

—Robert Gipe

≈