Interview

The editors at Still will present an extended interview with an Appalachian artist with each new issue. This inaugural issue features an interview with Jack Wright, filmmaker, musician, writer, scholar, activist, veteran, and Appalachian “cultural worker” (Jack’s label for himself). For nearly four decades, Jack has contributed to the story of Appalachia through his varied media contributions as a documentarian, oral historian, teacher, actor, musician, and archivist, among other things.

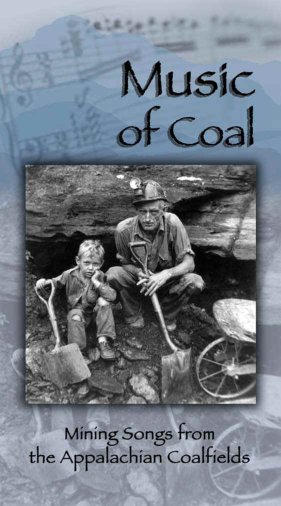

In 2007, Jack completed his work as producer and writer for Music of Coal: Mining Songs from the Appalachian Coalfields, a two-disc CD project that documents a century’s worth of coal mining music in the Southern Appalachians. His extensive, illuminating liner notes were nominated for a Grammy award. The project was supported by the Lonesome Pine Office on Youth in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, a delinquency prevention agency that has served families in Southwest Virginia since 1980.

In 1973, after service in Vietnam, Jack Wright went to work at Appalshop, the multi-disciplinary arts and education center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, where he founded JuneAppal Recordings and helped establish Roadside Theatre. Now a professor of film at Ohio University’s School of Film, all of Jack’s interesting and diverse life experiences have culminated in producing the Music of Coal.

Still’s poetry editor spoke to Jack shortly after the CD project was released. A slightly edited version of their conversation follows:

Marianne Worthington: Let’s start with some biographical information; where you were born, where you went to school, what your experiences have been in the mountains and with music.

Jack Wright: I was born in the hospital in Norton, Virginia, right next to High Knob, which is the tallest mountain in Wise County. It’s almost 5,000 feet, but of course, the hospital was down at the foot of the mountain. My Mother and Dad lived in a little apartment in Norton, but then they moved to the coal camp of Glamorgan where my Dad worked, probably when I was about a year and a half old. So my earliest memories are of Glamorgan and the coal camp, and of the company store, that kind of thing. Dad was a bookkeeper for Peerless Coal Company which ran the mine. That mine ran under the highway right there at Route 23, the big highway north to south from Michigan to Florida. The mine ran for miles out that way; it was a very deep, long, drift mouth mine. That was the first mine I ever went in. I snuck inside with a buddy when nobody was working. We went way back in there without any light.

And we had a very close, tight-knit family. My Mother had eight brothers and sisters and a lot of them still lived around Norton at that time. I had very close aunts and uncles, and that made a very warm and rich time growing up.

MW: Were you an only child?

JW: No, I was the first of three children. I was born in 1944, and my brother was born in 1948. My Daddy lost his job when Peerless closed the mine in 1951 or 1952. First he went to Illinois and got a job and didn’t like it. Then he went to Birmingham, Alabama, and got a job and then sent for us. So we moved to Birmingham when I was in the 4th grade. When I was in the 5th grade, my sister was born in Alabama.

MW: Did your father go to work for the coal companies in Birmingham?

JW: No, he worked as a bookkeeper for a construction company, so he didn’t have any particular allegiance to coal mining, although he greatly admired coal miners. When we moved back to Virginia four years later, he started doing independent bookkeeping for small, independent drift mouth mining companies.

So I started J J Kelly High School back in Wise County. I had always been interested in music so I started out playing drums, although I wanted to play guitar. (I didn’t get a guitar until I was 16.) I started out playing rock ‘n roll, and then later I started playing folk and acoustic music. As a boy, I wasn’t exposed to too much live music. You could hear it live on the radio, but as far as live performances, you might see it at the fair or at a band concert in the school auditorium. Occasionally, my band would play for dances, but there weren’t many live music venues when I was growing up—or at least ones that I was allowed to go to. Once when I was about 15 years old, we started playing in these beer joints where they bootlegged liquor—The Indian Head Grill and Mays’ Night Club and the Pink Room. We also played for our contemporaries at the Wise Club House, which was just a little place you could rent for community gatherings. We could rent it for eight dollars and charge a quarter a head to get in the door and have a dance party on Friday or Saturday night.

MW: Would you make your money back?

JW: Yeah, we’d make $10 or $12 a piece. When we moved back to Virginia, my grandfather had been killed in a car wreck, so we moved in with my grandmother on the family farm. We were about three miles outside of Wise, and it was really nice growing up on a little 50-acre farm next to an apple orchard. We had a small orchard, but there was a huge apple orchard next to our property—the largest apple-growing company/family in the county. I worked in that orchard, and we shipped apples to South American and Europe and all over the country. We packed them up and loaded them onto these cooled tractor trailers.

MW: Did you go to college after you graduated from high school?

JW: Yes, I went directly to Clinch Valley College. At the time, it was a two-year college. After I graduated, I went to Washington and worked, and then I got drafted. That was 1965. I spent from October, 1966 to August, 1967 in Vietnam. I came home and worked for about a year. Then I went back to college on the GI Bill while I drove a school bus. So I lived at home with my Mother, who was by then a widow, and my sister. While I was in Vietnam, my brother had joined the Army, which was a real bummer. He quit high school in the 12th grade and joined the Army.

MW: Was he in Vietnam too?

JW: No. My Mother talked to our United States Congressman and said she was a widow and that she had already spent almost a year worrying about me in Vietnam and she didn’t want to have to worry about her other son going to Vietnam. So my brother, who was a medic, ended up spending all his military time in Washington, D.C. We never found out that Mother had done this until years later when she finally told us.

MW: And where were you enrolled in college?

JW: By then Clinch Valley was a four-year school so I went back there. I was studying with Helen Lewis, and I took her first Appalachian seminar. She had raised money to teach a special seminar, so she had some money to put into education and have some experiential situations. She rented a big bus and we went to New York City and stayed a week during one Christmas break. And she had all kinds of guests come in from the outside like Harry Caudill, Earl Gilmore, a gospel singer from Dickenson County, Virginia, and Don West. Just a whole number of people who were involved in Appalachian culture.

MW: Did you have any idea then how amazing it was that you were witnessing all that?

JW: We all thought it was a very cool class, but we had no idea until later how new and unique and cutting edge it was. It gave us all an education in welfare rights, black lung, Miners for Democracy, about upheavals in the Union, about strip mining and about the past history of the region, how it had been bought by the outside interests and how those interests had contributed heavily to the poverty in the region.

MW: So it was in Helen Lewis’ class that you were introduced to Appalshop?

JW: Yes. She invited some people from Appalshop to come to her classroom and show some of the films they were making. And after I graduated from college, I went to Oxford and studied International Relations, travelled around England, Wales, and Ireland. When I returned, I got word that I’d received a Ford Foundation Youth Leadership Development Fellowship to study my regional culture. I got about $12,000 plus $3,000 travel money, and I lived off that money for about two years. I started recording multi-track audio, and some of my buddies had started a country/rock band, and we would self-record and promote our music.

Then I worked on a commune—well, it really wasn’t called a commune. I worked on Helen’s farm. She and some others had bought a farm in Scott County, Virginia, and wanted it to be communal living. I lived in a tent and worked on the farm in the garden and did some music on the side.

In 1973, I went over to see what possibilities were with Appalshop, and they hired me to come and work and develop my own ideas. My idea was to build a multi-track studio and start a record company. I had become interested in regional storytelling, too. So I got some grants from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Lily Endowment, and that money got JuneAppal Records and Roadside Theatre started. I was an engineer and the director at JuneAppal and was also touring with Roadside as a storyteller. We started playing theatre shows at schools and community centers and eventually festivals. That was a great lot of fun—lots of raw, wild energy.

But before I went to Appalshop, I’d become interested in putting on festivals, and I had put on four major festivals. They weren’t anything compared to today’s standards, but I had a lot of local people playing music in a festival situation before anyone in that county had ever done anything like that.

MW: Aren’t some of the cuts on Music of Coal actually taken from those festivals?

JW: Yes, the Dock Boggs cut is from the very first festival, there at Clinch Valley College. He performed “Prayer of a Miner’s Child” with the help of Mike Seeger, who also came to play. And then I had recorded Nimrod Workman before I went to work at Appalshop, and put his album out after I went to JuneAppal. Jean Ritchie came to one of my early festivals too.

MW: And when did you leave Appalshop?

JW: In 1985 I went to Ohio to graduate school to study film.

MW: So let’s talk now more specifically about the Music of Coal project. What is your relationship with the Lonesome Pine Office on Youth, the sponsoring organization of this project?

JW: I knew Paul Kuczko, the founding director. I had worked with him through Appalshop. He asked me to be one of the Humanities Scholars on a grant proposal he was writing for the Music of Coal project. After it was funded in July, 2005, he asked me to be the producer. He knew I had knowledge of coal mining songs. I knew Archie Green personally and Guy and Candie Carawan. I was fairly familiar with coal mining music, and Paul knew I had a background in it.

MW: What about the Charlie and Alan Maggard Sound Studios, where most of the music was recorded and produced?

JW: Charlie Maggard was one of those real soft-spoken men, a World War II veteran, who came back and worked briefly in the mines and knew it wasn’t for him. He grew up in a coal camp around Appalachia, Virginia. In the early 1960s he got interested in home recording and eventually he went into business. He started in his own house and then expanded as he became more successful. He brought his son in, Alan, who was also a coal miner. Their business did so well that he didn’t have to work in the coal mines anymore. I had known them since right after I came home from Vietnam. I had acted in the outdoor drama, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, at Big Stone Gap, and I got to know Charlie there. He was one of the musicians. Then when I had my own band, we recorded an album in his studio. They have eked out a living through the good times and hard times and managed to keep a local business afloat. Alan has a great ear for music.

MW: In the liner notes, you talk about some of the criteria you used for making the song selections, and one of the criteria was to use as much local talent as you could. What other criteria did you use? You must have had hundreds of songs to choose from.

JW: We had about 160 songs to choose from. It was really hard to narrow it down to the final 48. There were certain songs I feel had to be presented. For instance, I wanted “The Blue Diamond Mines” and I could hear Robin and Linda Williams singing that song, so I pitched that song to them. I could hear Ned Beatty singing “Sixteen Tons,” so I pitched that song to him, and he did it.

There was a committee of folks, of experts, who suggested songs we might use for the project. One example is “Coal Dust Kisses” performed by Suzanne Mumpower. She grew up in Kingsport [Tennessee] and now lives near Nashville. I heard a live broadcast of her singing that song, and I knew we had to have it.

MW: Did you ask anyone to write a new song for the collection?

JW: I asked Tom T. Hall if he would consider writing one. I had visited Tom’s studio in the back of his house and had a casual acquaintance with him for years. I wrote him a letter and asked if he would consider doing a song. He and his wife Dixie collaborated on a song and then recorded it for us. Ron Short had been thinking about a Blair Mountain song, and I think the impetus for him finishing that song with his co-writer came when we decided to do this project. So he worked to finish the song “Redneck War.”

MW: What other audio coal mining collections did you know about, and how does Music of Coal differ from those?

JW: There’s the Anthracite Collection and the Bituminous Collection that George Korson put together and was released by the Library of Congress [Songs and Ballads of the Anthracite Miners, 1947, and Songs and Ballads of the Bituminous Miners, 1965]. Recently, a young scholar put out a CD of George Korson’s work with West Virginia miners [Coal Digging Blues: Songs of West Virginia Miners, 2006]. I had worked in conjuction with Guy and Candie Carawan on a collection called Come All You Coal Miners that Rounder put out in the early 1970s. That was a precursor to the Coal Mining Women collection. I tried not to duplicate songs from these projects for Music of Coal. Of course, I had to include “Dark as a Dungeon” and I wanted to include Sarah Ogan Gunning.

MW: Wasn’t her song recorded at the Highlander Center?

JW: Yes. I was involved in the recording of that because I was at that workshop the weekend she sang that song at the Highlander Center.

MW: How does Music of Coal add to or contribute to the anthology of recorded music we have about coal mining?

JW: It adds to it in that by being specific to a region—to the Appalachian coalfields—it gives a view of the historical times of coal mining for almost a century. Even though the Edison Concert band [first cut on the project] wasn’t an Appalachian group, the idea of going down into a coal mine for a minute and 25 seconds gives us entry into the region. I wanted to be as diverse as possible. So there are songs written and performed by women and men, by African Americans, and there’s songs that represent key points in social movements and social concerns throughout the two-CD set. If you take each of these songs and put them all together, then you have a real good overview of some of the major historical events and developments of coal mining up to 2006.

MW: You teach your readers a lot about those historical events in the liner notes of the project, like the broad form deed, the Battle of Blair Mountain, the mine wars in Harlan, the roving pickets, the Yablonski murders. What did you learn from working on this anthology?

JW: First I learned about a whole lot of songs I got to know intimately that I didn’t know before. Another thing that kept coming back to me is how in this country we don’t really pay a lot of attention to coal mining until there is a disaster. I hadn’t really thought about that before.

Also, I learned specific things about specific events, like the Derby Mine disaster which happened in my home county about 1935 when 17 miners were killed. I learned some intimate stories about that. I learned about the life of Ed Sturgill who was a coal miner and entrepreneurial spirit who wrote and put out “’31 Depression Blues” which I really like a lot. I learned a lot about his career by talking with his daughter. His history was almost forgotten, so it was exciting to unearth him and put him back in the public spotlight. I located the tape that Sturgill had made for Alan Lomax, and nothing had ever been done with that. I was able to make a copy of those eleven songs and give it to Sturgill’s daughter. That was very rewarding for me as a cultural worker to give something back to this woman, the last living child of his, and she’s in her seventies now.

MW: What was the most frustrating or disappointing part of this project for you? What kind of obstacles did you face?

JW: I guess the most frustrating part was that it took a long time to get the information for some songs or to get permissions for some songs. The project took nearly two years, and so that was frustrating. Although, looking back on it now, I think it’s pretty damn amazing that it did get finished in less than two years.

MW: Was there a particular song that you just couldn’t get permission to use?

JW: Loretta Lynn’s “Coal Miner’s Daughter” was tangled up in some kind of legal process, so I couldn’t use it. But that song is so well known that in the end I felt it was OK not to include it. It was frustrating not to have a Rich Kirby song since Rich had recorded a lot of strip mining songs. Also, there were some songs that were not well recorded—field tapes with a lot of noise—that I just had to skip over. The technical quality just wasn’t good enough to use. That happened on several occasions.

MW: Do you think you might put out future volumes from all the songs you didn’t use?

JW: I don’t know. We talked about it during the elimination process. It got so hard to let go of some of those songs. There was a railroad song I wanted to include, but I was talked out of it. It was by a Vaudevillian called “Peg Leg Sam” Jackson whom I had met on the folk circuit. He was an incredible performer, a harmonica player and a dancer, with a peg leg. He harkened back to the days of string band music in the 1920s and 1930s. I really wanted to use his “John Henry” which is not really a coal mining song, but it sure took the railroad to get the coal out of the mountains. That was a hard one to let go of.

MW: Besides the Ed Sturgill story you talked about earlier, what were some rewarding or joyful moments for you in working on this project?

JW: Part of the joy as producer was getting phone calls or emails or letters from people after we released the project. One of the most rewarding experiences for me was to find out about how the song “Dirty Black Coal” was written. To finally locate Earl Sykes’ widow and to talk to her and her son about Earl’s work was really very exciting and rewarding. I also heard from Dwight Yoakam’s mother. Her father was the coal miner referred to in Dwight’s song, but she lost two uncles in the mines. To find out who those men were and how they lost their lives, to find the accident report and be able to send it to her was very rewarding—to communicate with her, not because she’s Dwight Yoakam’s mother, but because of her level of involvement in coal mining.

MW: Could we talk a little about some of the themes in this project? I’m struck by the dichotomy of themes in these songs: it’s either boom or bust, light or dark, hard times or good times, fatalism or celebration. I’m also struck by the recurring and haunting theme of starvation in these songs. What are some of the major themes that you see are illustrated in this anthology?

JW: Tragedy, struggle, overcoming, and organizing, certainly are major themes. The repetition of the same problems over and over, from the dangers of mining (there were two major mining disasters while we were working on the project—the danger is still there), man’s ability to become corrupt is also an inherent, recurring theme in these songs. And these themes have been there since the date of the first recording on the anthology, 1908.

MW: Can you tell me about the cover photo you chose for the Music of Coal?

JW: Oh that was another rewarding and exciting thing about this project. I had seen that photograph years ago, and it had become pretty well known around Eastern Kentucky. It’s such a beautiful picture; it tells so much. I was able to find out a little of the history of the photograph. Earl Palmer had taken the photograph and it was in the archives at Virginia Tech. I knew the father in the photograph was named Teach Slone, but I didn’t know the son’s name. All I had to go by was that the photo was taken in Knott County, Kentucky. I didn’t find out much, and I finally looked on a genealogy website and found a widow of Teach Slone. I called her up and she recalled the photograph and she told me the son’s name was Lyndel, the youngest of 12 or 13 kids. He was still alive and living in Hindman, Kentucky. I located his daughter first and she put me in touch with him. I was able to meet them at Hindman and give Lyndel a copy of Music of Coal before it was officially released. To hear his story was important to me. It was another story of struggle and survival. At the age of 11 or 12, he was in a roof fall that broke one of his arms and pinned him and his brother in the coal mine. He never went back in the mines after that. By age 12, he was saved from a lifetime of mining. He was only 4 years old when that picture was taken, and he was already by then a little coal miner.

MW: If you had to pick, which song is your favorite on this anthology?

JW: It depends on the day. I fell in love with a number of songs during the process. One week it would be “31 Depression Blues,” another week it would be “Roof Boltin’ Daddy.” Sometimes it’s “West Virginia Mine Disaster,” sometimes it’s “Which Side Are You On?,” You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive,” “Dying to Make a Living,” “Black Lung,” “Coal Tattoo.” There’s just so many songs, it would be too hard to pick just one. When I finally finished the project, I was listening to the music and had played through the first CD, and by the time “Coal Dust Kisses” came on the second CD, I just choked up. I was just moved to tears. I think that Sara and Maybelle Carter’s “Coal Miner’s Blues” is one of the most perfectly executed songs on the CD, in terms of timing and cleanness, harmony and instrumentation. I knew that song had to be on this project. And I’ll tell you one song I wanted to be on this collection, but I couldn’t find anybody to do it right: “Working in the Coal Mines,” [the 1966 Top 10 "Billboard" hit written by Allen Toussaint and performed by Lee Dorsey].

MW: What last words on the project can you give us?

JW: This collection gives a hundred year view of life in the mines and coal camps of Appalachia from many of the voices who lived it, and I want people to see the complex and bittersweet history of coal mining—to see how families have struggled to make a living. In good times and in bad, the music of coal is a reflection of the real life of mining families. The songs provide a record of the intense, life-changing experiences miners and their families have gone through. It can be such a hard way of life that many of the songs are heartrending, but I think there is also a lot of hope and happiness expressed in these songs too.

Read more about Music of Coal: Mining Songs from the Appalachian Coal Fields, produced by Jack Wright, here.