Trampoline

A Novel in five acts by

Robert Gipe

Reckoning

Part Two: Monster Birds

. . . Our Story so far . . .

Our narrator, Dawn Jewell, is fifteen years old when the story takes place. She lives on a ridge with her maternal grandmother, Mamaw Cora, who is protesting a strip mine permit application in their community. Dawn’s mother, Tricia, is a mess; her father is deceased; and her brother Albert is under the sway of her outlaw uncle Hubert. Dawn’s mother disappeared after Dawn stole the car she and her mother were riding in with Hubert on a beer run/trip to the hospital to Virginia. In our most recent episode, Reckoning 1: Dead Cow in the Creek, Dawn had two run-ins with her grandmother’s peculiar sister Aunt Ohio, spent the night with her banished grandfather Houston, cussed out bulldozer operator Keith Kelly, got drunk and despondent, and the ended the episode by jumping off a cliff.

Read Act Two, Reckoning, from Trampoline

Part One: Dead Cow in the Creek

Read Act One, Escape Velocity, from Trampoline

Part One: Driving Lesson

Part Two: Smother

Part Three: What Hurts

I jumped off the north side of the mountain. I fell so heavy. There was nothing light about me. I landed on a ledge ten feet below. I don’t know if I tried to hit the ledge or not, but I did. The ledge was dirt, moss, and rocks. Cold and wet, hard and soft. My first thought on landing was “I’m sorry. So sorry.” My second thought was “Oh shit, I’m going over the edge.” My weight took me forward, and nothing was between me and the valley below. The great white of the sky turned in front of me as I pitched forward and the stripped winter ridges rose up and then the road at the base of the mountain and I closed my eyes to fall. Why close my eyes, I wondered. Why deprive myself of the last marvel?

Something took hold of my legs. I stopped moving. All that I was was wonder, was winter still, angel still, and my ears filled with the sound of dripping water and a white pickup truck pushing through the slush on the road at the base of the back side of the mountain.

When I rolled over onto my side to see what had stopped me falling, the wet soaked me from my ribs to the bulb of my ankle. Aunt Ohio lay face forward against my hip and looked at me calm as if she were beside me on Houston’s sofa, as if I had just asked for a cookie or for her to change a channel on the television.

“Didn’t break your jar, did you?” she said.

I had not. Aunt Ohio squinted past me and I imagined a winged monster bird coming in for a landing behind me. Aunt Ohio took the jar of liquor from me and said, “Shame we couldn’t live right here.”

I didn’t know what to say. “What are you doing here?” finally came to me.

“I been coming here long before you was born, little darling,” she said. “Maybe you’ll tell me what you’re doing out here flying around,” she said, “scaring me to death.”

I sat up out of the wet. “ I didn’t know you were here,” I said. “I wouldn’t have scared you.”

Aunt Ohio smiled. She drank off all that was in the jar.

Clouds diffused the light. I could see Aunt Ohio clear as a bell. There was barely enough wind to chill us. The snow was coming again soon.

“Mother Nature,” Aunt Ohio said, and scooted back under the overhanging rock. She pulled twigs from her pockets. She had branches piled for a fire. “So you are a thief,” Aunt Ohio said. “I would give anything to be you.” Aunt Ohio took out her lighter and lit the little pile and bent to blow.

It was like a rocky bedroom there and I wanted to sleep by the fire with Aunt Ohio and her smoky eyes.

“I don’t have the energy to get stirred up,” she said. “I don’t have the stick-to-it anymore.”

I didn’t know what she was talking about.

“I couldn’t steal nobody’s man no more,” she said. “I don’t care enough to try.”

“I barely had enough to get up this hill,” she said. “Not enough to fling myself off it. I mean,” she said, “look at you. You jumped right off. Full of life.”

I said, “I only jumped ten feet.”

Aunt Ohio crawled to the edge of our little perch. She gathered up Mamaw’s pipe and pouch.

“We are what we are,” Aunt Ohio said. “Aren’t we?”

“I guess,” I said.

Aunt Ohio filled the pipe and struck her lighter. The tobacco flared. She smoked by her little fire. “The heart of a thief,” she said. She passed the pipe to me. “I suppose this is your pipe to smoke.”

I reached for the pipe and she pulled it back.

She said, “You didn’t steal it, did you?”

“No.”

“You didn’t steal it from your grandmother?”

“No.”

I snatched at the pipe. I did not like her treating me like some dandelion. She handed the pipe to me, its thin flat drawhole pointed towards me. I pulled at the pipe and coughed. The tobacco made me think of George Washington. So did Aunt Ohio.

“There must be some magic,” Aunt Ohio said.

“Why?” I said.

Aunt Ohio took the pipe back from me. “We sit at the top of the world with a roof over our heads,” Aunt Ohio said. “Magic enough in that, I suppose.”

She drew on the pipe and the smoke curled out in question marks.

“Come here,” she said, and she moved over on her rock to make room for me. “Call me Verna.”

“All right,” I said.

“Not Aunt Verna,” she said. “Just Verna.”

“All right,” I said.

“You can’t be careful,” she said. “You need to be careful. But you can’t.”

Birds flew by level with us. I would always like that.

“Don’t worry about your grandmother,” Aunt Ohio said. Her Ohio accent was back on full blast. I could hear her septum vibrating when she spoke. “You can’t pay any attention to her.”

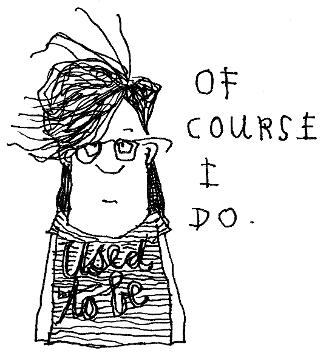

“I like paying attention to her,” I said.

Aunt Ohio searched my face. “Sure,” she said. “Of course you do. I’m not saying don’t. Not what I’m saying.” She stared at me like I was her reflection in a window she was cleaning. She wrinkled her brow, looking for the spot she missed. I expected her to lick her thumb and rub the spot off of me. But she didn’t.

“You must breathe,” Aunt Ohio said. “There is no substitute. The air going in, going out. Focus on that.” Aunt Ohio raised both her eyebrows as high as they would go. “If you do,” she said her raised finger like some twisted stick of Christmas candy, “there’s no stop to it. Natural. It’s what your body wants to do.” Aunt Ohio pulled on the pipe. “It’s like music,” she said exhaling. “See,” she said, “running her hand through the smoke, “like music.” She lay her arm across her knee. She pointed the pipe at me. “What is the most magical thing you’ve ever done?”

“Well, think.”

“I wished Albert would puke one time and he did.”

Aunt Ohio turned to the swirling snow, and then back to me. “It’s a start,” she said.

I asked Aunt Ohio had she done something magic.

“I’ve been around,” she said. She waved her arms, nearly hit me in the head. “Whoosh,” she said. Pulling her arms back into her lap, she said it again: “Whoosh.” She offered me the pipe. I didn’t take it. She put her arm around me. “It’s hard doing this,” she said.

She left her arm around me, and the snow came harder, but no winged monster bird came and picked out our eyes. It got colder, and her arm around me may not have been magic, but it was magic enough to get me and her both off that mountain in one piece.

~

Me and Aunt Ohio come off the trail where it met the highway. Gene had the Cadillac pointed off the mountain. Aunt Ohio hugged me, asked did I want a ride back to Mamaw’s. I said I didn’t. Aunt Ohio hugged me again.

Albert was sitting in front of Hubert’s and when he seen me, he jumped on a four-wheeler and rode up to where I was.

I said, “Albert I aint in the mood to fool with you.”

He said, “You seen Mom?”

Even though Albert spent all his time with Hubert, the mainest source of Momma’s problems—actually, I considered Hubert the total source of all our problems—I couldn’t deny Albert cared for Momma. Albert was a walking menstrual cramp, but Momma brought out the sweetness in him. He tried to keep it hid. But everybody could see it.

“No,” I said. “I aint seen her.”

“You want a ride back to Mamaw’s?”

I got on the back of Albert’s four-wheeler. Albert was thin, not fleshy like me. He wore a dark gray canvas coat. From behind, him and Mamaw had the same bird skull. He wore boots too big for him, gloves too big for him. He sped up and the cold air pressed our faces. He brought me to Mamaw’s carport.

“Where would Momma be,” I said, “if she wasn’t with Hubert?”

The four-wheeler seat creaked as Albert turned towards me. He shrugged. “You want to go look for her?” Albert said.

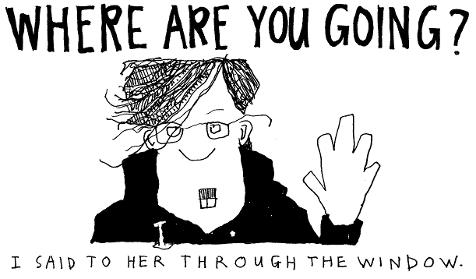

Mamaw come out in a hurry and got in the Escort.

“Mamaw,” I called, but she acted like she didn’t hear me. “Mamaw!” I called louder, but she pulled out of the carport. Albert hopped the four-wheeler in front of her. She stopped.

“Get in,” she said back through the glass. I got in and she pointed at Albert. “You too.”

Albert got in back. Mamaw took off, driving kind of crazy, which she does, but even more so than usual. When we got to town people were looking at us funny, and Mamaw threw gravel turning onto the Drop Creek road. She passed coal trucks when there wasn’t room. Me nor Albert said a word, not even to ask where we was going.

“They found your mother,” she finally said.

“Is she all right?” Albert said.

“They said for us to hurry,” Mamaw said.

“Who?” Albert said.

“Denny,” Mamaw said.

And that was all was said. Aggravating.

When we got to Denny’s, Denny and his daddy and a bunch of others sat on four-wheelers. I was glad to see Keith Kelly wasn’t there. There was two four-wheelers didn’t have nobody on them and Denny’s daddy said something to Mamaw I didn’t catch and Albert and Mamaw got on one four-wheeler, and I got on the other one. I felt strange on that four-wheeler by myself, all them other motors rumbling like men on the porch outside a funeral.

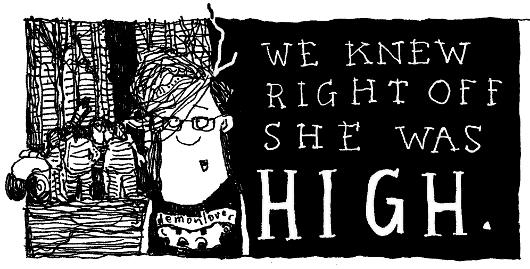

We took the four-wheelers the path I had taken when I stole one Thanksgiving. I wondered had Momma fallen down the same hole I had. I wondered had Momma fallen off the highwall. Had she OD’d or something like that, they would have taken her right to the hospital. The four-wheelers stopped. Mamaw was off hers first. She stared into the treetops. When I saw they was all looking up, I looked up too.

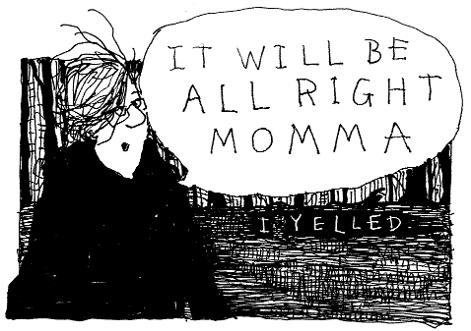

Albert yelled, “What are you doing?”

“What?” Momma said.

Momma looked crow-sized she was so high up in a poplar tree. I about got sick looking at her. Albert asked her again what she was doing.

“My business,” she said.

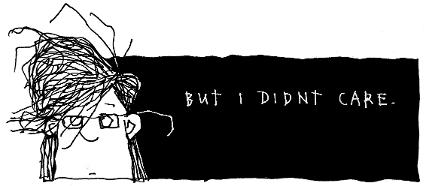

We were scared for her, but her buzz brought a tiredness, an about-wore-out-ness to our worry.

“Can you get down?” Mamaw said.

“I don’t want to get down,” Momma said.

“Aint no way she could get down,” Denny’s daddy said, “not til she sobers up.”

“Bless her heart,” somebody said.

Mamaw rubbed her hand across her face. Albert walked up to the tree, sizing it up like he was going to climb up there after her.

“You stay here, boy,” Denny’s daddy said.

“We should get Hubert,” Albert said. “Hubert could get her down.”

Nobody said nothing to that. A bird sang, sounding happy like a bird can even though a bird aint got brain enough to be happy. We were within thirty yards of the highwall.

“What are yall doing here?” Momma yelled down at us.

“What?” Mamaw said, and Momma yelled her question again.

Some of my cousins looked at each other like they was wondering the same thing, like they was thinking maybe they would leave Tricia Jewell up in that tree and go back and watch the ball game or maybe even do some chore for their wives.

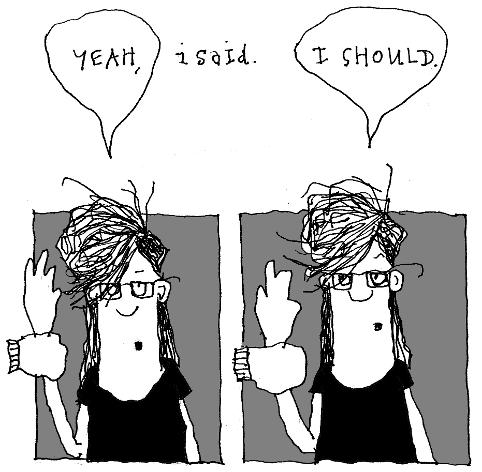

"I wished I could see what she was seeing. I wished

I knew what it was like to be on the level with a woodpecker’s call."

“Destruction!” Momma yelled. The sound hung in the air.

Somebody said, “How long you reckon she’s been up there?”

“Where’s her vehicle?” somebody else said.

“Maybe somebody brung her.”

“We could throw her a rope,” someone said. “I could go get a rope.”

“Why don’t yall go away?” Momma yelled.

“Pete’s got one of them harnesses he wears to work on power boxes up on poles for the cooperative.”

“Thought they used bucket trucks for that.”

“We could rig up a rope like a zipline, run her down that way.”

Denny’s daddy said that could work. “What do you think, Cora?” he said.

“Somebody’ll still have to go up there,” Mamaw said. Take her the rope, hook her up. Won’t they?”

“I’ll go,” Albert said.

“No,” Mamaw said.

Momma sang, “If the real thing don’t do the trick, you better think up something quick. You’re gonna burn burn burn into the wick….ooooh, barracuda.”

“I’ll go,” Denny said.

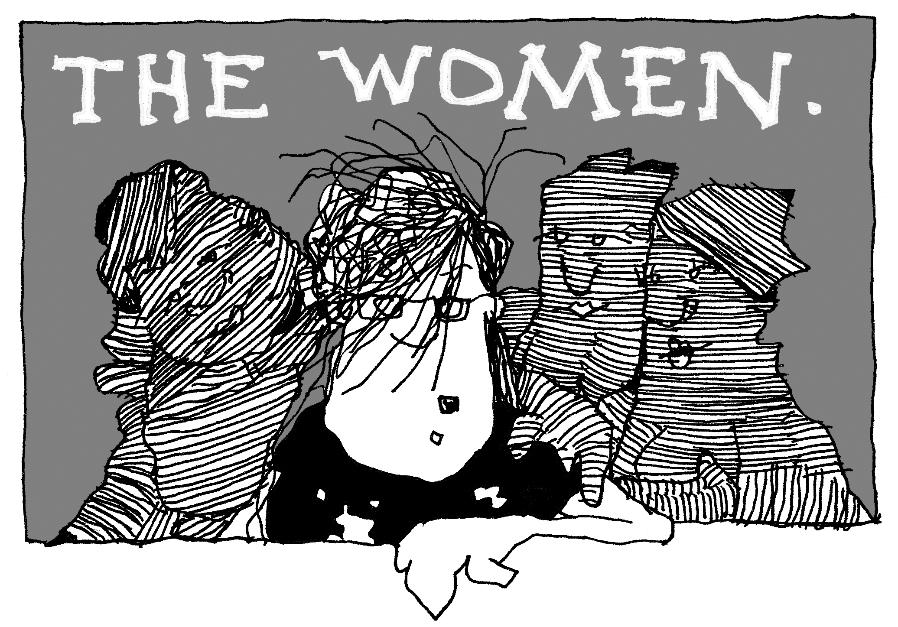

Momma was a good thirty feet off the ground. She sat in a ‘y’ where the trunk split. A woodpecker laughed. My mind flashed to the time Momma’s sister June took me to a movie in Kingsport had a Woody Woodpecker cartoon on before it. My mother looked out over the strip job. I wished I could see what she was seeing. I wished I knew what it was like to be on the level with a woodpecker’s call. The sky screamed blue. The tree branches surrounded my mother.

She waved at me. Light flooded her from behind. In a way, I did not want her to come down. I was glad to see her so high up. She had not escaped, but she was closer. And she was not so detailed to me there in the tree. I could not see vomit crusting on her cheek. I could not see the red swirl in the whites of her eyes like peppermint candy. All I could see was her beautiful stick-thin body wedged in the ‘y’ of the tree, the gold at the edge of her hair.

Momma turned away from the strip job to look the other way. When she turned, she slipped and nearly fell. Too much weight hit on that ankle, turned it. Momma cried out “OH!” and Denny’s daddy said, “Get up there and get her, Denny. Fore she falls out and kills herself.”

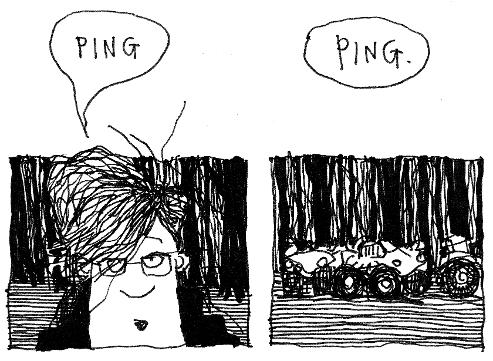

Denny threw off his coat. His daddy and his cousin had to boost him. His crack showed as he pulled himself up on the lowest limb. Denny seemed too heavy to climb that tree. He hitched up his pants and up he went. I seen a bear climb a tree one time on Animal Planet. It was like that. Big parts doing what they were supposed to do. Denny was a superhero, pulling me out of wrecked cars, climbing trees after Momma. He was our personal fire department. His shoulders were big, powerful. He climbed in a t-shirt with a picture on back of all the American presidents who had been cockfighters. The backs of his arms turned red and splotchy. Up he went. The sun came piling through the trees, turned the back of my eyes green and spotty. I could not see Denny and my mother. My nose filled with the smell of molding wood, my ears the pinging of the cooling four-wheeler engines.

I moved to where I could see Momma and Denny better. Momma reached for Denny like a baby waiting for its mother to lift it out of a stroller. The bark of the tree stained her cheek. Her skin was torn and the bark mixed with her blood. I could not see it, but it did.

“That tree aint gonna hold,” someone said. “They both coming down.”

Denny got to my mother and his daddy threw a rope up to him. “We might as well bring it down, before it comes with them.”

The men pulled on the rope and the tree, which was already falling, came with their pull. The wood cracked and split. My other cousin walked in front of me. My nose almost caught on the side of his head.

“Put it over yonder,” Denny’s daddy said.

My cousins dragged an old trampoline, its springs half-busted. I backed up. The trampoline stopped and the rope went tight and the spot where my mother and Denny were in the tree ended up directly over the trampoline and my mother’s legs come loose from the tree and they dangled, like two strings, like the fringe on a cowboy shirt, and Denny’s arms circled her ribs, and her shirt rode up and I could see her belly beautiful and rounded, like a perfect sausage, and Denny’s daddy went, “there you go,” and my mother come loose from Denny, from the tree, and she dropped to the trampoline and my cousins, her cousins, moved towards her, towards the trampoline and she bounced with an “oh,” and two cousins reached out to keep her away from the place where the canvas sagged from the broken springs. Denny yelled “move her,” and we looked up and heard the crack of the wood and I grabbed my mother, my too-light mother, by her ankle to make room for Denny to fall. When Denny fell onto the trampoline, the branches crashed on his back like a rain, like dumping water out of a bucket. He bounced and rolled and some of the branches smacked him in the face.

They tried to stand Momma up, but her ankle was broke. Denny didn’t say a word as the wood rained down on him. Albert went to Momma. Denny’s daddy and the other men went to Denny, looking up first to make sure nothing else was gonna fall and then they reached in and threw all the wood off Denny and he sat up on the trampoline, his elbows resting on his raised knees. Momma sat on a four-wheeler and asked one of the cousins for a cigarette and he gave it to her and she pulled out her own lighter and lit it. Albert put his arm around her shoulder. The woods were quiet then. There were eleven of us there in the room of trees, but it was quiet and clear and calm.

“Jesus Christ, Tricia,” Mamaw said. She did not walk towards Momma. She stood with her hand against the trunk of the tree Momma had been up in. Denny sat on the trampoline and got him a cigarette too. He did not get upset with Momma or anybody or anything else. I didn’t know what to think, what to do next. I felt like maybe I ought to run off.

Up in the tree where Momma and Denny had been looked like lightning had struck, looked like a lot more time had passed than actually had.

~

“Momma, what were you doing up there?”

On the way home from the hospital, I sat in the back of Mamaw’s Escort with Momma. Albert sat up front. Mamaw drove. Mamaw always drove. Momma had her head in my lap and a cast on her ankle. The road made me sick. Momma smelled of the tree. Her hair was greasy. She needed a bath. A long one.

“I care too,” Momma said quiet.

“Do what?” Mamaw said.

“I care too.”

Albert turned and looked at us. “About what?” he said.

“About strip jobs. About things getting torn to pieces.”

Mamaw didn’t say anything right off. Then when I thought she wasn’t going to say anything at all, just let it go, she said, “I know you do, Tricia.”

~

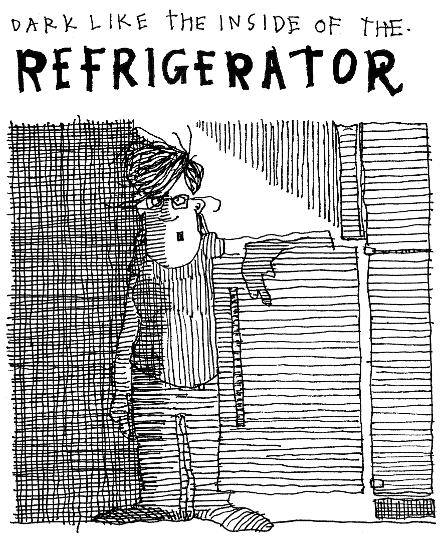

Momma had her arm around Albert’s shoulder as they made their way down the hall from Hubert’s kitchen. The kitchen table and counters looked like bears had been in there, packages tore open, jars busted in the sink and on the floor, everything edible licked clean. My cousins ate Hubert out of house and home every time he got put in jail. I followed Albert into the room my mother kept for herself in Hubert’s house. It was the only room without boards or cardboard or foil over the windows, the only room where you could see out. The rest of the house was sealed up tight.

We set Momma down on a ratty couch somebody got out of a dump and Momma had cleaned and covered with a pink quilt. Albert disappeared, brung Momma back a glass of orange juice. Momma couldn’t settle. She bent and stretched and twisted.

“Put some gin in that juice,” she said. “Sose I can settle.”

I could barely hold my own head up. I closed my eyes and nearly fell over. I put my head on Momma’s shoulder.

“You want to take a shower, Momma,” Albert said. “Dawn, run her a bath.”

I didn’t think I had the strength to give my mother a bath, but I did. The bathtub was new, but cheap and plastic—and dirtier than she was. The water came good and hot, scalded the nasty off the sides of the tub. I rinsed it out, run more hot water. When it cooled a little, I picked Momma off the commode and set her down in the tub. I kept her bad foot out of the water. She smiled for me to touch her, smiled as I rubbed the soap on her. I ran the rag over the thin skin covering her ribs. Her chest felt like a pair of panty hose with a bird cage stuck up in one leg. At first I wished I’d just stood her up in the shower. I didn’t want to be giving her a bath.

Man voices refilled the kitchen. They came down the hall, beat on the door, but it was locked. They went back to the kitchen. When I finished giving Momma a bath, she pulled on a t-shirt of Hubert’s, walked in her room, got in her bed, and turned out her light. I stood in the bathroom door and watched her across the thin hall. Albert come up from the kitchen where he’d been sitting with whoever it was come in.

“She down?” he said.

I didn’t say anything. He went in the room and closed the door.

“Come here, Dawn,” somebody hollered from the kitchen. “Come here, Dawn Jewell.”

I didn’t acknowledge. Whoever it was kept on, but I still didn’t acknowledge. Finally they quit. Albert’s hand shook when he closed the door on Momma. I followed Albert out on Hubert’s porch. Albert slouched against the porch rail.

“Why do you come out here to smoke?” I said. “They all smoke in the house.”

Albert squinted and didn’t say anything.

“Momma will sleep now,” he said half a cigarette later. “Be lunchtime tomorrow before we see her.”

I didn’t say anything. There wasn’t anything to say.

“You remember when she first got in the cake business?”

“You couldn’t get up before her. Couldn’t go to bed after her. That woman could stir.”

Daddy used to call her “that woman” the way Albert did.

“It aint getting no warmer, Albert,” I said. I wanted him to take me home. Albert flicked his cigarette out in the yard. He moved like he had a bad back, like an old man. I followed him. We got on the four-wheeler. He started out onto the Trail, out towards Mamaw’s. It was pitch dark now, crystal sparkly dark night. A truck come up to us and stopped. The two men in the truck chewed tobacco. I could see their jaws working through the window glass. Big one driving rolled down the window. “What are you doing?” he said to Albert.

“Taking her home.”

“Hey, Dawn.”

“Hey.”

It was Crater. I didn’t hate Crater.

“You’ns should come over,” Crater said. “Decent’s coming.”

Decent Ferguson was a big woman. Older. Gone to college back in the wild free days. She was gray-headed but still had freckles like a girl.

“You want to go?” Albert said to me.

“Don’t matter.”

Crater had Pickle Peters with him. Pickle Peters didn’t have no neck. His hair came down his forehead even with his eyes. That’s the way his momma cut it. Covered up the fact he had one eyebrow run clean across the front of his head. Pickle Peters was twenty-eight and never been to a barber shop. He raised his chin at me when he seen I was looking at him.

“We’ll be up there after while,” Albert said.

Crater pulled off without rolling up his window.

“Well,” Albert said, “you don’t want to go, do you?”

~

Crater had a high house. When I got off the four-wheeler, I felt like the house might fall over on me. We walked the wooden steps up from the underneath-the-house carport, through the darker-than-dark dark. When we walked in Crater’s house, Decent was on the edge of her chair, her arm reared back like she was fixing to throw something.

“I drew back the skillet,” she said, “and let it sail. ‘whoopwhoopwhoop’ it went. Skillet landed ‘thunk,’ right in the small of his back, and he went down like he was shot. I thought I’d killed him. Momma came out went berserk.”

Crater’s wife Priscilla covered her nose to keep snot from blowing out she was laughing so hard.

“Did you get your hamburger back?”

“Yeah, I did. He still had it in his hand. Knocked out cold and never turned loose of that hamburger.”

“He was a sight,” Priscilla said getting up off the hard chair she was sitting on. She went to the kitchen.

“Albert,” she said, “they’s beer and pop in the cooler. Chili in that pan. Yall help yourself. Hey Dawn.”

Just as I sat down, Decent got up to smoke.

“Crater won’t let us smoke in here no more,” Decent said. “How about that? World gone wrong, aint it?” Decent hacked. “I need to quit anyway.”

The men slapped Albert on the back. “What say, little bad-ass?”

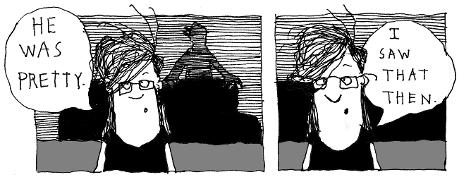

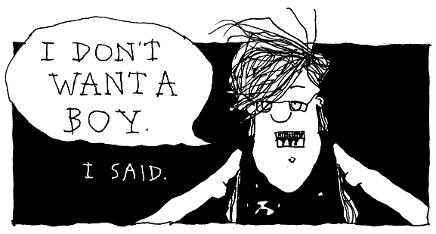

"Bottle-white blond hair and black-ringed eyes. Her smooth cheeks said

she hadn’t been running with this bunch long."

There was one other female there. She was drawn back into the sectional sofa, lost in her buzz. Bottle-white blond hair and black-ringed eyes. Her smooth cheeks said she hadn’t been running with this bunch long. They all looked at me. I had no doubt they knew about me stealing the truck and the car, but nobody said anything. Albert got up. Brought me a beer.

“How tall are you?” Pickle said.

“Five ten.”

“You done growing?”

I twitched my shoulders.

“Put your hand up here.” He raised his hand, and I put mine flat against his.

“God damn,” he said. “That’s a big old Sasquatch hand.” Pickle held me by the wrist. “Where’d you get that big old Sasquatch hand?”

I tried to pull my hand away, but Pickle held on tight. I said, “I don’t know.”

Pickle said, “You play basketball?”

“Not really.”

“You ought to.”

“What are yall doing,” Decent said, blasting into the room on a wave of cold air, “playing patty cake?”

“I’se looking at this woman’s monster hands.”

“Turn her loose Pickle,” Decent said. “You aint got no business handling her like that.”

Pickle reminded me of Cinderella, which I wish he hadn’t cause soon as I thought of Cinderella, soon as the idea of him come on my mind, here come the real Cinderella tramping through the door.

Decent said, “We found this here going through your garbage cans, Crater.”

“Shoulda shot him,” Crater said.

“I wadn’t going through nobody’s garbage cans,” Cinderella said.

“Look who’s here,” Pickle said. “Your old chauffeur.”

“Well, I’ll be goddamned,” Cinderella said, “I ought to beat your ass or kiss you one, Dawn Jewell.”

“Why you gonna kiss her? I heard she got you throwed in jail.”

“She did,” Cinderella said, sniffing down in the chili pan. “If I’d been home that night instead of in jail? I’d of still been in jail and not for no drunk and disorderly. They’d a jacked that jail up and throwed me under it.”

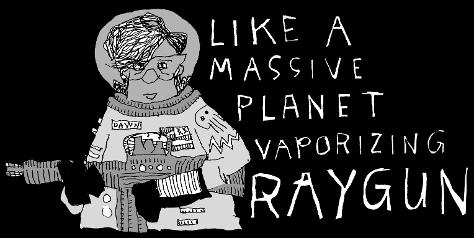

Cinderella come sit between me and that other girl. Keith Kelly stood facing me. He must have come in with Cinderella. He shook his head looking at us. Keith Kelly and his wavy brown hair. He could barely keep it under his hat. When I looked at Keith Kelly my stomach tightened, like there was somebody standing on a tire iron screwing down the lug nuts of my guts. I tried not to look at Keith Kelly, but when I did, my eyes locked down on him like a ray gun.

He didn’t say nothing to me, but I could tell he was feeling his power over me. Him and his wavy brown hair was feeling their power over me same way every square-ass schoolteacher, every girl knew exactly what everybody else is wearing to school that day soon as her precious feet hit the floor in the morning, every kid who had both parents at home, got what was on his Christmas list, slept in the same bed in the same house every goddam night of his goddam life all had power over me same as Keith Kelly and his wavy brown hair. I narrowed my eyes at him and he didn’t do anything, sat there like a stone, like a clock, like a face on a campaign billboard.

“Hi Keith,” said that girl with the black ring eyes, “How you doing, baby?”

Keith Kelly didn’t say a thing, took in what that girl said like it was money somebody owed him. That girl settled back in the sofa and knocked Cinderella’s hand off her leg when he tried to pet her with it. She hadn’t quit on pretty Keith Kelly. She set looking at him like she would be making another run at him before the night was out, like he best not turn his head. Pickle Peters asked Keith Kelly for a cigarette. Keith Kelly said he didn’t have one.

“Pickle, you don’t smoke,” said the black ring girl.

That house was dark, too dark. Nobody could see I still had mud from jumping off the mountain on my pants, still smelled of gas from the four-wheeler ride back to Denny’s, still had the smell of gauze in my nose from taking Momma to the hospital.

“All is well. All is well.” Priscilla was trying to quiet somebody down in the kitchen who was going, “All is well. All is well.” There was a wood box yawning open like a drunk in church on the coffee table. Box was black-lacquered with brass hinges, red velvet inside, somebody’s dope box, a baggie full hanging out of it.

“Want to burn one?” bleary Pickle said to me.

I twinkled my fingers in front of Pickle’s eyes told him to get back in his box. He raised his hands up in my face, hands like wood, and I got hold of his mother-trimmed bangs, a fistful of his hair, and I slapped his grizzly cheek with my other hand.

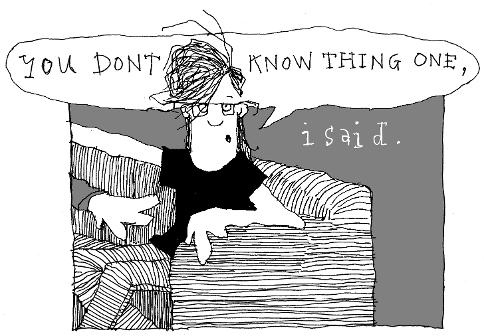

“You don’t know what I’m feeling,” I said to Pickle Peters gape-mouthed face.

They all laughed and the lugnuts tightened again in my belly. I turned loose of the front shank of Pickle Peters’ hair. Nasty thick three-colored stuff like straw. Not like hair. Not thing one.

My mother’s hair was getting like Pickle Peters hair. It wasn’t soft like it was even two years before. I’d noticed that giving her a bath. There wasn’t much softness in my life, wasn’t much softness in life in that fuckpot county of mine, and it seemed then like the softness was going from it, fast and furious like smart kids leaving after high school graduation. Someone let a long wet fart and they all laughed. They was wanting to laugh. They didn’t care what at. Keith Kelly lit a cigarette. Pickle Peters set up like he remembered where he left a hundred dollar lottery ticket.

“You told me you didn’t have no cigarettes,” he said.

“Hush, Pickle,” Priscilla said.

Pickle said, “Boy, don’t you remember?”

Keith Kelly blew out, waved the smoke and fart smell from in front of him.

“Boy,” Pickle stood up, “Tell me I caint have a cigarette now.”

“God almighty,” Priscilla said, and hit Pickle in the eye with a cigarette. “Shut the fuck up.”

“YOU DON’T SMOKE, PICKLE,” that black-eyed girl said again.

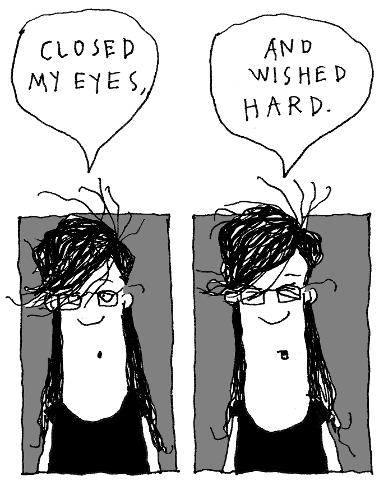

I wished hard for my momma’s soft hair.

“How’d you get mud all over you?” Cinderella whispered in my ear.

“Jumping off a mountain trying to kill myself.”

“Why’d you do that?” Cinderella said.

“So I wouldn’t be here having this talk with you.”

“Boy,” Pickle was still standing. “What’s the matter with you? Can’t you hear what I’m saying?”

They all knew then Pickle was going to go ahead and get redneck. Didn’t matter if I’d just announced I’d tried to commit suicide or told them I was carrying Dale Ernhardt’s baby. Pickle was out and gone.

“It’s a Friday night,” Pickle was rocking back and forth now. “And you don’t need to be lying at no nice get-together like this.”

“Pickle,” Priscilla said, “That’s the last time I’m telling you to shut up. You don’t need to be a total asshole. Not every weekend.”

“It aint me being assholish,” Pickle said. “It’s this Barbie doll motherfucker.”

Keith Kelly gave Pickle a cigarette. Pickle tore it open and blew the tobacco back at Keith Kelly.

“God Almighty,” Priscilla said.

“I been following you,” Cinderella said to me. He thought he was talking low, but everybody heard.

“No you aint,” I said.

A pointy-eared dog, white with chocolate spots come hopping out of somewhere.

“Yeah I have,” Cinderella said. “Soon as I got out of jail I come right straight looking for you.”

“What for?”

“Cause I wanted to see you again.”

“How old are you, Dawn?” The room went quiet when Decent asked. Her eyes were two humming outboard motors pushing a boat across summer waters. I water-skiied behind her outboard motor eyes, rope tight pulling me across a rough glass lake under a paste-gray sky.

“Cinderella, you filthy pervert,” Decent said.

“She’s older than that,” Cinderella said. “Look at her. She’s a giant.”

I looked at Albert. He grinned. Decent pulled me up and away from Cinderella. She put her arm around me.

“Cinderella, you can’t tell time. How you know how old she is?”

They all laughed. Decent turned me loose. I sat down on the far end of the sectional. Decent poured drinks all around, put beers in people’s hands, sat down beside me. She kicked Cinderella’s feet off the coffee table. “Play something, Pickle,” she said.

Pickle strummed his guitar, warmed up his low voice. “I hear the train a-coming. It’s rolling round the bend. And I aint seen the sunshine since I don’t know when.”

We sang that song and Ring of Fire and then Decent sang “make me an angel that flies from Montgomery.” The blond girl got down off the sectional and curled up on the strandboard floor. Keith Kelly sang “Sam Stone.” I glanced over at him out of the corner of my eyes. No hat on, brown hair wavy and full there on the couch with them other men.

“You act like you’re her lawyer, Decent,” Keith Kelly said.

“Who?”

“That one,” Keith Kelly said pointing at me.

“I aint her lawyer,” Decent said. “I’m the judge.”

The blondie girl woke up off the floor, laughed—“HA!”—and fell back to the floor.

“That’s what I say,” Crater said. “Ha.”

“You laugh,” Decent said, “but I know them girls got Cinderella put in jail. Dawn was right to get out of there. Them women diseased.”

“We didn’t catch no diseases,” Cinderella said. “They wouldn’t have nothing to do with us. They was trying to kill us.”

“That’s what I’m saying,” Decent said, beer bottle bobbing on her knee, “no point waiting on yall.”

Everybody laughed. Pickle Peters elbowed Cinderella, made him spill his beer into the sectional.

“Goddam yall,” Priscilla said.

“That don’t make it right to steal a man’s car, nor another man’s truck,” Keith Kelly said.

“She was just having her a Thelma and Louise moment,” Decent laughed.

“Decent, what are you,” Keith Kelly said, “some kind of lezzie?”

“Do what?”

“You heard.” Keith Kelly rose up. “You aint her momma. You aint her friend. And it’s obvious she aint normal. I think you’re doing her your own self.”

I had heard all this before.

“Why don’t you shut your mouth.” Oh dear lord. Albert speaks.

“Where’s your man, Decent Ferguson?” Keith Kelly said. The sleeping girl sat up again, big grin on her face, eyes dancing to see what happened next.

“Strong woman,” Keith said. “I’ll show you strong.” Keith Kelly was drunker than I’d thought.

“Will you?” Decent said.

“Decent, don’t,” Priscilla said.

“Yall need to settle down,” Crater said.

“I don’t care to show you,” Keith Kelly said, “not one bit.”

Pickle Peters dropped his guitar. The strings went ‘bonnnng’ through the hollow wood body. I leaned forward.

“Dawn,” a voice came from behind me. “Dawn don’t look right.”

My vomit splattered on the pointy-eared dog, rained all over Keith Kelly. I threw up again. Everybody scattered, except for Decent and Priscilla.

“Here honey,” the bottle blond put a bucket in front of me. “Aim for that, doll baby,” she said.

“How much had she had?”

“I aint seen her drink nothing.”

“That girl aint right.”

I heaved again. The vomit came in strings. I don’t know what it was or where it came from but it sure felt good.

“I aint never seen nobody throw up smiling like that.”

~

I woke up at Decent Ferguson’s place, in her quilt-thick bed at the back of her little house dwarfed by its big ass garden plot. She sat beside me on the bed, looked right at me.

“Why don’t you talk to somebody about what’s going on?”

“And say what?” I said.

“Well,” Decent said, “You don’t think you need to talk about car stealing and jumping off mountains to somebody?”

“That don’t mean nothing,” I said. “Bad day.”

Decent’s lips flatlined. “You reckon?”

Decent’s eyes was brown. Her lips was great big. Her hands was meaty, red rough and raw. She sat with one foot propped on the other. I looked around Decent Ferguson’s place. I could smell her bad sulphur water. It was in the piles of clothes laid at the end of the bed and in every chair. She had animals made out of painted gourds on shelves near the ceiling looking down at me. Folded quilts heaped up in every corner and Loretta Lynn album covers were tacked all over the walls. Fist City. Don’t cat around with the kitty.

“So who would I talk to anyway?” I asked Decent Ferguson.

“Well,” she said, “Let me think about it.”

“Can I talk to you?”

“You can talk to me,” she said. She didn’t mean it. I could tell.

"Why won’t my mamaw tell me what she’s thinking?”

“Have you asked her?”

“Why do I have to ask her? I’m supposed to be the kid. Why do I have to ask to be raised?”

Decent Ferguson said she didn’t know.

“You just need to do what is best for you,” Decent Ferguson said. “There aint no heroes, no oracles.”

“What’s an oracle?”

“Like a fortune teller.”

The space behind my eyes hurt. I said, “You’re not helping me.”

“I’m sorry.”

The clock clicked over to twelve, over to Sunday morning. I started to cry.

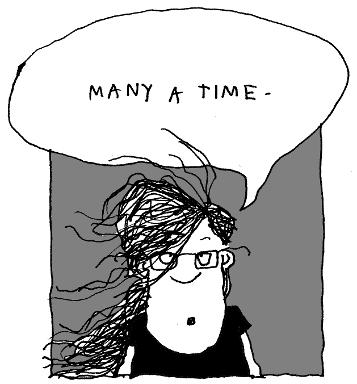

"Decent was freedom to me. Not chained by man nor kid.

She rode her own personality like it was a horse."

“It’s crazy,” Decent said, “that anybody would ask me for advice.” Decent got up and dug through drawers, ran her hand behind the stuff on top of her refrigerator. “Shit,” she said going through the pockets of coats and sweaters on hooks behind the kitchen door.

“What are you looking for?” I said.

“Cigarettes.” She found a pack in a sweater pocket. Two left. She lit one and said on the inhale, “Maybe your aunt June, maybe that’s where you need to go.” Decent exhaled. “You remind me of her.”

“How?” I said.

“I don’t know,” Decent said. She drew again on the cigarette, looking at me. “Around the eyes.” I had my glasses off. “You’re dark. Your eyes are always moving too. June’s eyes were like that. Are, I guess.” Decent drew again. The smoke swirled again. Always smoke in the air. Always forest fire season. Decent wiped her nose on the back of her hand. “So you seeing anybody?”

My heart dropped when Decent asked that. Decent was freedom to me. Not chained by man nor kid. She rode her own personality like it was a horse. She wasn’t good looking. Lumpy face, crooked smile. But in that moment I saw I had to have a boy to have something to talk about. I didn’t want a boy.

Decent took the last cigarette out of the pack and looked at it. She lay it on the table, rolled her fingers back and forth over top of it. “That’s all right,” she said. “I don’t blame you. Not one bit.” Decent Ferguson coughed, waved her hand in front of her face like she was waving away smoke, or bugs, but there wasn’t neither one in the air in front of Decent Ferguson’s face.

Decent Ferguson sat up that night and talked to me. She showed me where her arm was burned pulling records and quilts out of her last trailer fire. She explained to me who was in the pictures on her walls. There were black men with guitars and tambourines and groups of people wearing baseball gloves and shirts that said SPAM on them. There were always men in the pictures. Decent Ferguson pulled out a sweater she had made. It was a great big sweater and a blue I didn’t like. But it was homemade and I liked that and she put the sweater in a plastic bag and gave it to me which I liked too. I thanked her and set out for Mamaw’s.

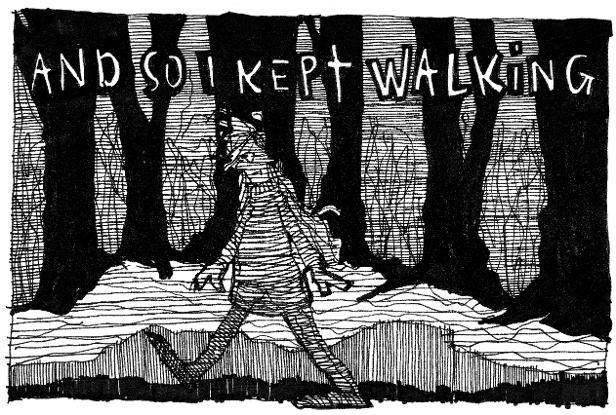

The snow turned to rain. Plain old rain. I walked through it in Decent’s sweater, which felt like it could hold it all, every drop. The road was slick but not shiny, the only light shot out as usual. The rain came so hard I knew nobody was going to look out their windows, much less come out. It was going to rain on me and nobody else. No vehicles, only rain coming down like bucket after bucket of cat guts.

My clothes got so full of water and I was so tired I felt like maybe I had turned to water, that I should just lie down like water, stretch out on that cracked black asphalt and drain away to the creek, to the bottom of the mountain. If it had been one degree warmer, that is what I would have done—just laid right down and turned to water and flowed right off that mountain. But as it was, it was too cold.

End Part Two

Read Act Two, Reckoning, from Trampoline

Part One: Dead Cow in the Creek

Read Act One, Escape Velocity, from Trampoline

Part One: Driving Lesson

Part Two: Smother

Part Three: What Hurts

~

Author's Statement:

I was born in North Carolina in 1963 and was raised in Kingsport, Tennessee, a child of the Tennessee Eastman Company, Pals Sudden Service, and the voice of the Vols, John Ward. My dad was a warehouse supervisor and my mom a registered nurse. I went to college at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina where I was a DJ for a student radio station I helped start. I went to graduate school at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and got a masters in American Studies. I worked as a pickle packer, a forklift driver, and eventually landed a job as marketing and educational services director for Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky, in 1989. At Appalshop I worked with public schoolteachers on arts and education projects.

I met my wife, Robin Lambert, at a conference in 1992, and we bonded over an interest in rural communities and an opposition to school consolidation. We married in 1993. She is my heart's delight. Since 1997, I have been the director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland, Kentucky. I am one of the producers of Higher Ground, a series of community musical dramas based on oral histories and grounded in discussion of local issues. I am also a faculty coordinator of the Crawdad student arts series. I have had fiction published in Appalachian Heritage and have attended the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman every year since 2006.

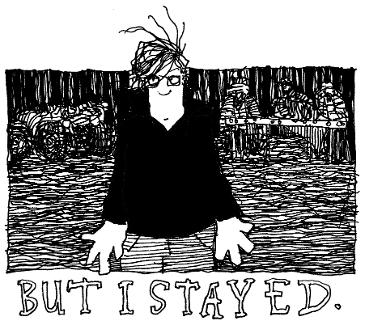

I have been working on the characters in Trampoline since 2006. The narrator is Dawn Jewell. She lives in a coalfield county in eastern Kentucky, and is in high school when the story takes place. She's having a rough go of it.

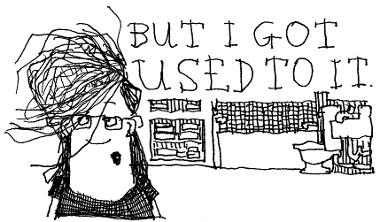

The sound of people telling one another stories is the most precious sound in the world. Trying to catch that sound on the page is my favorite part of writing. Most of my favorite writing—Flannery O'Connor's stories, the novels of Richard Price and Charles Portis—seems to me written by ear. When writing is going best for me, it's like taking dictation from voices I hear in my head. As far as the drawings go, I have drawn pictures all my life, much longer than I have written stories, and with more compulsion. Trampoline is the first time I have seriously tried to integrate fiction and drawing. I love episodic storytelling, especially the great HBO series—The Wire, Six Feet Under, Deadwood, etc.—and have enjoyed thinking about how to break a story into semi-coherent pieces.

—Robert Gipe

~