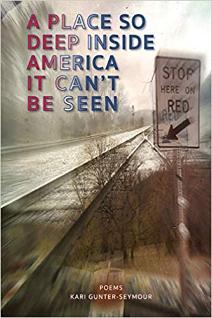

Book Review

A Place So Deep Inside America

It Can't Be Seen

Appalachia is often used as the scapegoat for America’s political and cultural ills, and many journalists have come searching for ways to place blame upon its inhabitants. This poetry collection by 2020 Ohio Poet of the Year, Kari Gunter-Seymour, strikes back at the narrative of problematic Appalachian people and a region in peril. Even the book’s title makes clear that Appalachia is a part of America, not some “other” to be ostracized, and that the true Appalachia is a place that “can’t be seen,” as it’s far deeper than any journalists’ eyes have pried. The author also calls southeastern Ohio home, an area not frequently realized as Appalachia, even by Appalachian folks, giving yet another layer of meaning to the title.

The collection is divided into two parts; the first section speaks to histories, and the second section exists more in the present life of the speaker. The backstory provided by the first sixteen poems helps to place the reader in the speaker’s life, allowing a deeper appreciation for the latter half of the book. Throughout this incredible collection, the Appalachia that “can’t be seen” is revealed in details of the landscape that a photographer’s camera might miss, in the relationships between family and friends, and in the connections made between the speaker’s home in Appalachia and the world at large.

The collection’s first poem is a near-echo of the title. In “I Come From A Place So Deep Inside America It Can’t Be Seen,” the speaker makes the reader privy to the “real Appalachia,” a place where magic happens, where “A moth presses wings / thin as paper against my window, / more beautiful than I could ever be,” where “Everything alive aches for more.” The details of the Appalachian landscape however, don’t just stop at the external. The reader is also given a glimpse into the speaker’s own internal landscape, a space in which “my cousins / called me ugly, enough to make it last.” This juxtaposition of external and internal ecologies spread like kudzu throughout the pages of Gunter-Seymour’s work.

Much like the Appalachian landscape aches beneath mining and fracking and commercial farming, readers are shown a speaker who aches along with it, burdened with the loss of passed-down “mountains ways,” “piles of feathers and angel bones,” and “all the things our grandmothers buried.” This pain, however, also radiates outward, forging the previously mentioned connections with family and friends. In “Because The Need To See Your Daughter Overcame All Sense Of Reason,” the speaker depicts this incredibly difficult situation involving her son:

You fresh out of the VA hospital,

your story untold so long it re-booted

old terrors—brittle photos

of mortar fire and keening mothers.

Me the tightrope mother who rides

her unicycle along the edges

of our sunny avenue, parade waving

to the crowds, trying to blink

the red out of swollen eyes, the overbite

of my jaw scraping my lower lip.

So often, military service is admired without critique of its potential to do long-lasting damage, even if members survive their service. Gunter-Seymour pulls no punches and provides an unabashed look at what the horrors of war can do to a mother, her child, and the larger community.

Jessica Cory is a lecturer in the English Department at Western Carolina University and a PhD student in English at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She is the editor of Mountains Piled upon Mountains: Appalachian Nature Writing in the Anthropocene (WVU Press, 2019). Her scholarly and creative work has appeared in North Carolina Literary Review, A Poetry Congeries, …ellipsis, and other fine journals. Originally from Appalachian Ohio, she now lives in the southern Appalachians, calling the mountains of western North Carolina home.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________