Interview

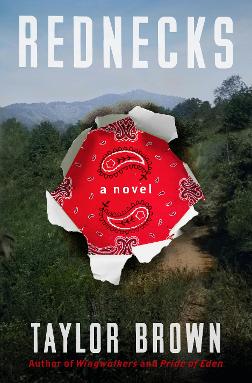

Jody DiPerna interviews Taylor Brown, author of Rednecks

When author Taylor Brown first heard about the Battle of Blair Mountain, his first instinct was that he needed to know more. He wanted to know more about this fight for workers' lives in the mountains of West Virginia, where one million rounds of ammunition were spent, bombs were dropped on Americans on American soil, there was guerrilla warfare and machine gun fire. The natural storyteller in him wondered how he could tell the story of king coal assembling the collective might of law enforcement, hired private guns and civilians deputized into vigilance committees for their war on working men.

In his novel Rednecks (St. Martin’s Press, 2024), Brown wrote the story from multiple points of view, going bit by bit, one decision leading into the next, with resistance, care and cruelty folding into one another like the mountains of West Virginia. He told me this book felt like a calling, mostly because this story has been muzzled.

"It was so suppressed. Even 10 years after it happened, when the WPA (Works Progress Administration, part of the New Deal) was going around the state and interviewing folks . . . the West Virginia governor wrote FDR and said, 'we don't want the WPA writers mentioning the Hawks Tunnel disaster, the battle of Blair mountain and a steel worker strike,'" Brown recalled.

Rednecks takes place in the southernmost edge of West Virginia, along the Tug Fork River, the border with Kentucky in Mingo and Logan Counties, the heart of coal country. After World War I, workers in the area began joining the United Mineworkers. Coal companies retaliated against unionizing. Even hints of organizing would find workers fired, blackballed and evicted from their homes in the company towns. Workers who took up the union cause were targets for violence at worst and, at best, they were blackballed from working in other mining operations. Corporate malfeasance in the Appalachian coalfields just means it's another day ending in “y.”

In the summer of 1921, as working families lived in tent colonies in the Logan County hills, the one law enforcement officer who took up for the miners instead of taking aim on them, beloved Matewan Sheriff Sid Hatfield, was assassinated by coal company men on the steps of the courthouse in neighboring McDowell County. The conflict exploded into the bloody Battle of Blair Mountain.

Brown first heard of the resistance of the rednecks from his friend, Jason Frye, to whom the book is dedicated. The miners wore red bandanas around their necks, hence the term “redneck,” a sobriquet being reclaimed now by some as a badge of honor and symbol of resistance.

"Jason grew up on the mountain looking, not for arrowheads, but for shell casings, looking for trenches from the battle," Brown said. "He started feeding me this history, and I was just blown away, because I had not heard about it at all. Here's a battle—the largest labor uprising in US history—and it's not a story that everybody knows."

I spoke with Brown in the summer (2024), weeks before the Democratic National Convention in mid-August, but we both thrilled when West Virginia activist and creator John Russell took the stage at the DNC, resplendent in a plaid short-sleeved shirt with pearl snaps, and told the crowd, "They called us rednecks back in the 1920s because striking workers from all different races wore red bandanas around their necks as they fought and died for respect and a living wage. Their fight yesterday is our fight right now. Right now."

Brown himself grew up in a small town on the Georgia coast and now lives in Savannah, far from the coal fields of Appalachia. In order to do justice to those who struggled and fought and died, he researched intensively, steeped himself in first person accounts and archives, read numerous histories, and even rode his dirt bike to trespass on the land itself. All of it paid off in writing that is full of exquisite and righteous depth of feeling.

they worried about blowback from the powers that be and the coal companies, even still." ~Taylor Brown

Of course, there has been plenty of writing about Blair Mountain. When Miners March by William C Blizzard, Thunder in the Mountains by Lon Savage, The Devil Is Here in These Hills by James Green, and The Road to Blair Mountain by Charles B. Keeney are essential nonfiction accounts. Diane Gilliam’s prize-winning poetry collection, Kettle Bottom, and John Sayle’s independent film Matewan are also devoted to telling about the Blair Mountain mining wars. However, this story has not come to life in fictionalized form since Denise Giardina's groundbreaking 1987 novel, Storming Heaven. Even with the efforts of these writers and the incredible people at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, some stories are lost to time.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead

_____________________________________________