Book Review

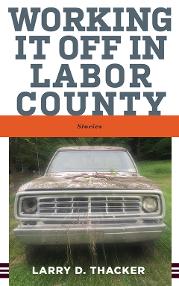

Working It Off in Labor County

The residents of Larry D. Thacker’s fictional Labor County, somewhere in Kentucky, have a few things in common. Many of them know each other, making guest appearances in each other’s stories. And they’re all outsiders in some way, in this fictional place they share, struggling with—or against—the situation they’re in, looking for salvation, answers, or maybe just peace. They hope for the best, although they have learned from experience not to expect too much.

Their stories are gathered in Working It Off in Labor County, Thacker’s first collection of short fiction, after three books of poetry, two poetry chapbooks, and a nonfiction book. His fourth collection of poetry and a short fiction collaboration are forthcoming. [Editors’ note: Read new short fiction by Larry D. Thacker also in this issue.]

Thacker opens the collection on a light note, with a history professor doing time for trying to steal his own Civil War memorabilia collection back from the museum he loaned it to. We meet a mother whose son’s visions have set the two of them apart everywhere they have lived—so she has to come back to her hometown, hoping to find understanding. Thacker gives us several visits with Ed, an ex-arsonist whose plea for God to save him during a job gone wrong is being answered more literally than he expected. But that doesn’t make it easy to understand what the new voices in his head want him to do. Other residents of Labor County make it hard for Ed to turn over a new leaf—a familiar concept to anyone from small communities where folks will always remember what you used to be, no matter what you try to change. We also spend more than one visit with Uncle Archie, whose love for curiosities to fill his Odditorium keeps his customers, and his eager nephew, guessing.

Like Uncle Archie, Thacker has an eye for oddities and absurdities, the details that breathe life into a tale. He is an acute observer of detail, and his stories have smells and textures, and the little strange details that make a story live and breathe. In “Brotherhood of the Mystic Hand,” a band of Vietnam buddies hold their annual reunion weekend after the death of a member. But this isn’t just a group of aging men getting together to relive an important experience. These are men whose talisman is the severed, mummified hand of one of their members. Their reunion is held in a seedy bar next door to a realty office, decorated with an armored personnel carrier (named Carlene II) displayed in the parking lot, and owned by a man named Tank with a peg leg. The details and quirks add up until you can practically smell the sweat and the cheap beer, and a desperate kind of brotherhood.

Or take “Uncle Archie’s Acquisition,” our first visit to the Odditorium. Uncle Archie doesn’t just have a two-headed snake on display. He has “a fully formed seven-foot-long, two-headed rattlesnake named the Lucifers, once the pride and joy of the snakehandling members of the Shaketown Hollow Holy Temple Church until one head bit the other during a tent revival in 1978.” Thacker gives his readers plenty to work with.

“Now the fire was nearly on him, slow stalking, upside down, crawling across the blackening kitchen ceiling and catching the curtains of the back door and window he’d crawled through.”

Larry Thacker, Working It Off in Labor County

Chelyen Davis' fiction has appeared in literary journals such as Appalachian Review and Still: The Journal. Her non-fiction essays have appeared in the Bitter Southerner and other media outlets. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart and Best of the Net awards, and was the recipient of the Appalachian Review’s Denny C. Plattner award in 2016 and winner of Still: the Journal’s 2014 fiction contest. Chelyen is a native of Southwest Virginia, currently living in Richmond, Virginia.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________