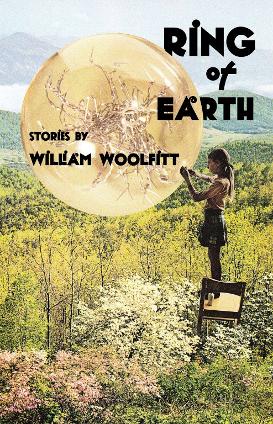

Book Review

“‘I love it here and now I hate it too,’” says Leah, one of the protagonists of “In the Hollow.” For varying reasons and in different ways, one can imagine most of the characters in Ring of Earth, William Woolfitt’s first full-length story collection, saying much the same. Time and again, they seek a way out of their circumstances, not so much because they don’t love the land, but because they are desperate for connection they cannot find there. Take Leah and her boyfriend Sam, who move several times trying to find a suitable home. When at last they do, they find their relationship with each other strengthened as well. Unfortunately, the place turns out to be literally poisoned; this in turn strains the relationship. In other stories, such as “What the Beech Tree Knows,” the connection to place is strong despite the absence of human bonds. Still, one cannot help but ask what will happen to the semi-orphaned boy when his uncle finishes logging out his parents’ land. Will the boy burn with fever like the doctor in “Fire Season”?

“Fire Season” serves as an especially strong example of Woolfitt’s ability to write a wide cast of characters. The principal figure in this story is not in fact the doctor, but rather his oldest daughter, Suse. She wants nothing more than to take over her father’s practice but is constantly rebuffed, told she should marry, perhaps become a teacher. In an era where women are choosing the bear over the man, where a man who makes millions kicking balls tells women their greatest joy lies in being barefoot and pregnant, the empathy for Suse’s plight comes as a soothing balm, even as we despise the patriarchy that seeks to restrain her.

Indeed, the protagonists of these stories are young and old, male and female, Appalachians living in a variety of places and times. Readers might find themselves following present-day tourists as they visit a wax museum or an aquarium, or they might accompany immigrant miners who self-segregate by race, ethnicity, and nationality as they take a break from their work underground. In one story, white, Black, and Native American characters work together on a plantation where most of the crops have failed; in another, a teenage boy tries to find his way in a world where his mom works as a cashier at Walmart while he assists his uncle’s mail-order bride.

Woolfitt, who has authored several books of poetry, displaysboth an ear for language and a gift for finely observed detail throughout Ring of Earth.

He is his wife’s arms when she clutches him, he is the wings of her shoulder blades when she turnsfrom him. Her voice and dreams are the only gold he knows, he is the gold of her, the gold of sundownand Elberta peaches and poplar leaves and moss that grows between roof-shakes, he is gold in her hands.He is motes of hay in barn light, grass-bits caught in a ray, in a spill of gold that spears through the crackedgray boards. He is cedar smell, and the soft bed, and the odor of wood-smoke caught inside the house.

As for himself, Jake doesn’t know what he wants, doesn’t know which of the world’s equations he shouldplug himself into. He is fourteen. There is a strain in him, a yearning for things he doesn’t have words for,as if he’s starting to upheave, crack apart until he’s webbed with lines running in all directions.

Laura Dennis is a Kentucky writer, mother, Mimi, and professor with family roots in northern Appalachia. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Change Seven, Northern Appalachia Review, The McNeese Review, Still: The Journal, and The Red Branch Review. She reviews books for several publications and co-edits book reviews for MER. She enjoys music, photography, hiking, and spending time with her friends, family, and pets.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________