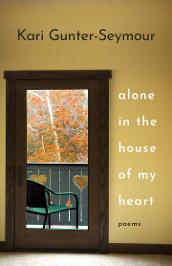

Book Review

Kari Gunter-Seymour is an important voice, writer, and presence in the Appalachian region—and fast growing beyond. Grounded in Appalachian Ohio, her stated personal and professional mission is to uplift her native ground and culture and bring attention to its history, struggles, sass, and diversity, the ground from which her blessings (and hardships) flow. In her second full-length collection, Alone in the House of My Heart, she is the singer and the sung, the healer and the healed, the mirror and its reflection—the full-throated work she has been coming to, both in generational melancholy and affirmation of life, “hellbent for butter,” despite its multiple woundings.

For most of us, no matter our experiences, the mother wound is often the deepest we must tease and pry out like a splinter from the woodpile, embedded in skin and psyche. All other choices and experiences flare from this central relationship, for good or ill. A girl weighing her mother’s critical eye and tongue, Gunter-Seymour writes, “I come from farm folk, short, stocky / built to dig a ditch, throw a bale. / My mother bargained: / lose five pounds, earn Barbie.” Still, this bond is strong and endures, despite the mother/daughter reflection in troubled waters, and compassion rises to the surface: “Cracked as a broken mirror and all its mess, / her hours decline to halves, halves to minutes, / an empty frame all that remains, / of the what, the where or the not of her.” Then we are brought to the stark and poignant present, the time of Covid, where, like so many anguished families, she cannot visit her wasting mother in the nursing home: “Other daughters hold her now, / masked, silvering threads of life / cradled in their latexed hands.”

Appalachian artists of all genres tend to infuse their work with a sense

of place, warts and all. That close relationship of the personal and the literal landscape runs through this collection with sorrow, immediacy,

and stubbornness . . .

Although Gunter-Seymour’s poems are rooted in family and their dire history rippling through her and her son’s lives, her native southeastern Ohio is equally her motherland, “the blood and bone smell of it,” scarred by coal barons, food insecurity, fracking, and abuse of opioids. Appalachian artists of all genres tend to infuse their work with a sense of place, warts and all. That close relationship of the personal and the literal landscape runs through this collection with sorrow, immediacy, and stubbornness to withstand and heal, to be the last truth teller left standing. In “To No One in Particular,” she writes:

I take solace in considering the age

of this valley, the way water

left its mark on Appalachia,

long before Peabody sunk a shaft,

Chevron augured the shale or ODOT

dynamited roadways through steep rock.

So much here depends upon

a green corn stalk, a patched barn roof,

weather, the Lord, community.

We’ve rarely been offered a hand

that didn’t destroy.

Still, her roots are comfort and balm: “These mountains cradle me / from every side.” The land imprints her with “scars the shape of shattered / hearts stamped into our elbows and knees.”

The musicality of her work leaps off the page, as in “harsh as a sip of threepenny gin,” “your mouth desperate with teeth,” “the hur-uff of a doe,” “scant as an eggling fallen from / its nest,” and “March winds blow bitey.” Not only an enviable use of language, but that of a master singer/poet in her finest opus, beating out shape notes to the congregation, to any who need to tune ear and heart to both embrace and brimstone.

What is history anyway,but a conversation we’re born intowithout context, a string of songsabout heartbreak, a universethat made us from its shattering and dust?

What she comes to, and what we glean in poem after poem, is “the wide, wide reach / of love.” She reminds us that we are all broken or scarred in some way and, like the archetype of the wounded healer, how we use our wounds to light the path for ourselves and others is ultimately our life’s purpose.

Poet, playwright, essayist, and editor, Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and the copy editor for Chapter 16, Tennessee’s literary website. Widely published, her fifth poetry collection is Candescent (Iris Press, 2019). Five of her plays have been produced by Flying Anvil Theatre in Knoxville, where she lives and gardens. She is an eighth-generation Tennessean.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________