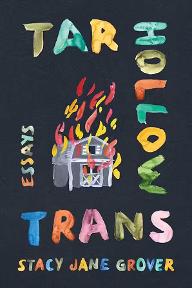

Book Review

As a queer Appalachian, I’m constantly looking for writing in our community—not only for my sense of belonging, but also for other LGBTQ-identifying folx to find solace, community, and kinship. Stacy Jane Grover’s new collection of essays, Tar Hollow Trans, provides a new glimpse of trans representation in our community, but also addresses the complications that come along with being trans in Appalachia. The most powerful aspects of this book describe these complications and shortcomings, but also the need to just exist without justification from those inside and outside the region.

The memoir begins with Grover’s struggle as an Appalachian, but also as a transgender woman: “I became invested in learning how my transgender existence informed and was informed by my upbringing in southeast Ohio, considering this nascent Appalachian identity. I wanted to find the missing piece of my belonging.” What is so powerful about Grover’s discovery of these intersectional identities is that they’re not easily pinned down, but rather that she “let the me of the past remain unruly, resist my attempts to capture or represent or interpret her, resorting her agency.” In these essays she’s not limited to one self and often cuts off her own analysis of places, spaces, or ephemera of Appalachia to demonstrate the multifaceted, complicated nature of her identity and the identity of the region.

In the beginning of the book, Grover writes about how all her identities are questionable. She is from Ohio, but is it Appalachia? Her own gender identity falls into a space that is dangerous because of recent discriminatory government policies. However, she, like many Appalachian writers, find solace in the land. In her chapter “Lancaster is Burning,” she escapes from the celebratory fairgrounds and capitalistic mall. She notes:

The land is the land is the land, and while it has never been open, it has opened me. . . . The day carries

a peaceful density that cuts through the usual tension. No protestors come to intimidate; no preachers

with bullhorns come to shame. For an afternoon the tension rage on outside the confines of these bodies

melded in hill, shade, and tree.

We see here and throughout the text that the land is constantly changing as is her own identity. It is a place where she can go home for respite and recovery, but it, too, has suffered turmoil through human interference and development. Despite this changing of the land, the mountains still serve as a place where trans lives not only matter but where trans folx can live and thrive sustainably.

In these stories, Grover weaves personal narrative, history, and theory

in a way that both enlightens and touches readers with a new voice

that has been missing in Appalachian literature and activism for so long,

a voice reclaimed by a return to story, place, and a deep, self-analytic identity.

I can allow Bessie and my younger self to remain unwieldly, to rest in the silences of archive and

memory. Maybe from that place I can write narratives that shift and morph into something a little

less certain, ones that stop deploying the I, the we, in service of some mission. I can write us into

that position, which is nowhere, into something that fails to tell a legible story.

Travis A. Rountree is assistant professor in the English Department at Western Carolina University. He has been published in The North Carolina Folklore Journal, Journal of Southern History, and Appalachian Journal. He is the author of Hillsville Remembered: Public Memory, Historical Silence, and Appalachia’s Most Notorious Shoot-Out (University Press of Kentucky, 2023). Hailing from Richmond, Virginia, Travis has lived in Appalachia for most of his life. He is an avid fan of old time, bluegrass, and country music and lives in Sylva, North Carolina with his two kitties. He serves as the president of the Appalachian Studies Association, chair of Sylva Pride and a board member of Blue Ridge Pride.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________