Book Review

The prose poems in this Abecedarian collection, where the titles follow the order of the alphabet, function like the “fisheye” lens mentioned in the opening poem. Time, place/space, and point-of-view contract and change as image and metaphor metamorphose. These poems are both surreal and plaintively, emotionally resonant, evoking lyric poetry’s most heartfelt traditions as well as the risk-taking ethos of prose poetry. They are organized both associatively and through the sheer momentum of the poet/reader/speaker moving through time: “When it rains, it rains on everyone, and I am drenched in memories. Merciful Jesus, let’s go only forward, never back.”

These poems inhabit a self-aware space gesturing constantly toward “[waking] from a dream of dreaming” where the speaker “cannot tell where I am in levels of reality” though she knows “I am still somewhere.” They are, as they tell us, all of these realities and dreams at once. They contain multitudes. Here is a list of images from the book that could be considered definitions of what the book is trying to be:

“a deep cave filled with wonders by other names,”

“gaps in deep spacetime,”

“yolks of pure gold,”

“water not water,”

“[j]azz . . . cascading as it rolled,”

“a cherry smash of sleeping and waking,”

“stories like shuffling cards,”

“a live chicken in a paper sack,”

“an absence pointing to the thing,”

“an edge culture,”

“[l]ike moving water, my tiger, tiger,”

“the moonlight of this moment,”

“[s]hy black bears,”

and “the odd-numbered third harmonic of a xylophone.”

They are often concerned, like Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, with the tactile associative magic of language itself, pushing up against the limitations of words and shooting through to the other side, into a playful ur-tongue where the prose poems become an abstracted definition for their individual titles. The poem “Black Pepper,” for example, is filled with percussive, open vowel sounds in the the words “toppled,” “high tops,” and “cinderblock” and is a bit a cinderblock itself in its visual presentation on the page, containing strata of memory and association as it skips from the speaker’s childhood cat “Tiger” (who weaves in and of these poems in true cat-like fashion), to a childhood art project, to a speaker “fascinated by adults who kissed,” and who “dodged red ash my dad flicked from his Kents.” The slant rhyme present between “kissed” and “Kents” shares a sonic logic with the “[b]lack pepper” that “looked like dirt flecks and stung my tongue.” To paraphrase Hopkins, the images/metaphors in this collection could be said to rhyme, as well as the words themselves. In the end, the speaker in “Black Pepper” vows “to give up writing so I can write. To give up protestation, so the giant cat can tip me over.” These poems ask the reader for the same surrender, with the hope, with the ideal being an openness, an unsteadiness, a return to wonder where we too could be tipped over into something grand and strange. They are, to quote Stein, all “[l]ovely snipe and tender turn, excellent vapor and tender butter.”

A poem titled “Concern” features, fantastically, a “little stingray creature that flies like a sparrow.” In “Contested Chicken” a “fully plucked and headless” chicken “[raises] a raw wing” to “ring” the speaker’s “bell.” In “Giant Black Bear” a “giant black bear [occupies] all of space” and then “[steps] over the speaker” as it goes “stomping in the distance.” The reader is admonished in the next poem to “pull up the rope” attached to “an anchor that might snag far beneath the boat.” Reader, the boat might be the poem, but so may the anchor.

Consider “New Testament,” a short exploration of the virtues of metal paperclips and how the speaker’s “mother left a paperclip to a certain page in her New Testament,” though which page/verse is never revealed. Or the linguistic playfulness of “Odder,” a riddle about an “Otter” but a play upon both the characteristics of this creature (“slicker than a flicker and fetcher to fishes”) as well as the very American pronunciation of the “t” sound as the “d” sound. Hankla’s work is like the “dream sickles” we encounter in the poem “Saving Lives”—a joke, an image, a meta-commentary on the form and formlessness of language, where the poet-speaker is busy “combining syllables into tinctures.” On one level these poems operate like that old nonsense-sense song “Mairzy Doats,” which is quoted in the book. They ask us, “Wouldn’t you?/ “wooden shoe.”

These poems defamiliarize the world so that we can encounter it anew, in all of its beauty and absurdity (“I don’t understand west highland terriers. . . . I don’t understand my heartbeat.”) They are, as Edward Hirsch described American prose poems, “kin to parable,” constantly upending our emotional and imaginative sense of the world.

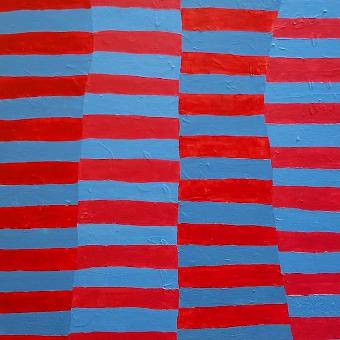

There is a connection to be made between these prose poems, which even echo the shape of a painting in their rectangular or square block shape on the page and her paintings dense with a color palette that is both vibrant and complex. The repetitions and joyfulness found in these paintings are also found in these prose poems. Both luxuriate in the writerly/painterly process, in the nuts and bolts of the artform itself. Hankla seems to be saying, “Here is a game about slant rhyme. Here is a game about how the eye relaxes and focuses on patterns”

Annie Woodford is from a mill town in the Virginia Piedmont and now lives in Deep Gap, North Carolina. She is the author of Bootleg (Groundhog Poetry Press, 2019). Her second book, Where You Come from Is Gone (2022), is the winner of Mercer University’s 2020 Adrienne Bond Prize and the 2022 Weatherford Award for Appalachian Poetry. She was awarded the Jean Ritchie Fellowship in 2019.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________