Still: The Journal: You’re a graduate of both the prestigious Clarion Workshop and a traditional MFA program. Could you talk a little about how your training in these programs benefited you as a writer?

Ashley Blooms: I’m definitely one of those people who could be a perennial student. I really enjoy learning in all kinds of classroom environments even with all the frustrations that can attend them. And after I graduated with my bachelor’s from EKU, I still felt like I had so much more to learn, so applying for MFAs felt like the natural next step. Those three years at Mississippi gave me, more than anything, the time and space to take myself seriously as a writer. To really imagine and make a plan for what a creative life would look like for me. It taught me how to sift through various opinions on my work and how to find my own voice amongst others, how to meet deadlines and how to manage my time and expectations. And it introduced me to so many incredible writers, many of whom I’m still in touch with, and one of whom I very happily married. But my work is such a blend of different genres—including literary realism, fantasy, horror—and while I wrote in those genres during my MFA I still wondered what it would be like to be in a workshop environment comprised only of folks writing speculative stories. So, I attended Clarion about two months after I graduated with my MFA. Clarion is an incredibly intensive program, very concentrated, and I was absolutely exhausted most of the time, but it was also really wonderful. There’s definitely an almost manic feeling in the air at times, because you’re drafting stories every week and reading tens of thousands of words of fiction every night, and you’re being spurred on by all this amazing work and these incredible instructors. And because of the time constraints, I often had to get out of my own way and just write. The inner critics couldn’t keep up with the Clarion pace so I tried things I wouldn’t have tried before and went for stories I’d avoided in the past. It was freeing, in a way, as well as challenging. So the MFA and Clarion were very different experiences, but I feel like I grew from both of them tremendously.

Still: You’ve been asked this question before, but because we publish writers and artists with some connection to Appalachia, we’ll ask you to talk about how place has influenced your work, especially since you gravitate toward fantasy in your writing. What are some aspects about being raised in eastern Kentucky that lend themselves to the fantastical?

AB: I feel like eastern Kentucky is absolutely brimming with magic. I think that’s one of the reasons I love to write speculative fiction set here because I’m not sure that everyone can see what I see when I look at my home. I attribute that perspective to a lot of things, like the storytellers in my own family. Growing up, I heard all kinds of stories about people I knew and people long dead—about the time Papaw saw a ghost at the bend in the road and that woman in the holler who hid gold bars under her floors and that distant uncle who murdered his wife. Characters were all around me, and many of their stories were unfinished or had gaps in them where people disagreed—all these empty or contested spaces just waiting for someone to come along and piece them together. And there’s such a fascinating mix of religion and folklore and superstition at home—my grandparents kept a family Bible in the living room but Papaw would also sign the cross when a black cat crossed his path and we weren’t allowed to play in the creek during the dog days (though I’m still not entirely sure which days are canine and which are not). Even coal mining is strange. I watched my father leave home early in the morning, clean face and slick hair, and then return covered in coal dust, his clothes coated with earth, like he was slowly turning into the mountain he mined. Then I grew up and learned what black lung was and how the dust literally gets inside the miners, becomes a part of them. Doesn’t that sound like a spell to you? Some awful magic? My world felt laced with strangeness, like the boundaries that shaped the regular world were really more like suggestions. I don’t have to look far at all for strange and wonderful stories in these hills.

Still: A similar question, then: You’ve written before about your experiences in the Holiness church. Could you talk about how those experiences inform your life as a writer?

AB: I think I’m still untangling the impact that being raised Pentecostal has had on me and my work. The church was such a staple of my childhood, so it only makes sense that it’s going to appear in my writing, and especially when those early experiences were so unique. As a child I regularly watched the people in my life become something else inside that church. One moment preaching, the next stomping the ground, dancing, calling out in a language I couldn’t understand. Women would writhe in their seats, heads tossed back, hands balled into fists. People running down the aisles, shouting, sometimes screaming. All because they had been touched by the Holy Ghost. That’s what it meant to commune with something divine—to be reshaped, remade.

I see those experiences all over my work. Not just in the explicit ways, although I do often write characters who are faithful, or struggling with their faith, or who are adjacent to the church. But I also see it in the way I write about bodies as permeable things always on the cusp of transformation and in the way that my characters are often faced with forces beyond their reckoning and how they never walk away from these encounters unchanged. I even feel it in my language at times—this kind of build, this rhythm, like a preacher reaching the height of their sermon. I haven’t attended church since I was a teenager, but I think its influence is still with me now, and with my work.

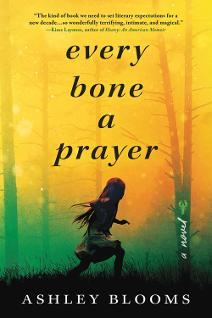

Still: We used the words “fantasy” and “fantastical” above to describe some of the elements in Every Bone a Prayer, but in other interviews, you’ve said your writing is more closely aligned to “fabulism” or “slipstream.” Could you clarify these genre terms for our readers within the context of your own work?

AB: I’m pretty general with the terms I use to describe my work—fantasy, fantastical, fabulism, slipstream, any of those feel fine to me. The only term I don’t personally use is magical realism, which seems to be the dominant term for work that blurs reality and the term that most people are familiar with. But, from my understanding, magical realism or magic realism was originated by Latin American authors who often used the genre as a tool of subversion against colonization. It’s a term and a genre that has a very specific history and resonance that I simply can’t claim.

Still: We admired how you so carefully (and slowly) reveal time and place and worldview through objects in Every Bone a Prayer (a cordless phone, strip mining, doing housework in a denim skirt) but on the other hand, the fantastical is introduced almost immediately. What was your process in thinking about how to juxtapose the reality and the magic in your story?

AB: In most cases I like to think of the fantastical elements in my work like dandelions growing up through a sidewalk—they’re elements that emerge naturally from the world, even in places we least expect them, or places they didn’t first belong—magic like a weed. Sometimes that means I have an idea I want to toy with—like ghosts—and then I think about what themes or story or character would exist around that idea. What do ghosts mean? What do they represent? What do they evoke? And sometimes it goes in the opposite direction, finding the character or world first and then seeing what kind of magic emerges from that particular blend of personalities, desires, dreams. And sometimes they come together for me—a character and their ability, a world and its magic. The same was true for Every Bone a Prayer. I don’t consider the fantastical elements separately from the reality because, for me, they’re twined together from the very beginning, and then it just becomes a process of building them alongside one another, revealing them both a little at a time.

Still: Misty, the main character in your novel, is so complex for a 10-year-old! One of her many gifts is being able to hear the energy and inner life—the stories—of both living creatures and inanimate objects. Tell us about the origins of the idea of granting Misty this gift, which really is one of the guiding forces of the whole novel.

AB: Similar to what I said above, my magic systems often emerge from or are tied to character and theme. The fantastical is a tool I can use to explode an idea, to see it from many angles at once, to complicate something that’s already happening in the book, or to introduce new elements. For Every Bone a Prayer one of the major themes I knew I would explore was the way that trauma shapes identity, so I wanted a magic that seemed to emerge naturally from Misty, her life, and what the story was trying to say. The idea of names seemed like the perfect fit—a way to examine what makes us who we are and how those things change when we experience trauma, loss of autonomy, shame. And then, how we recover, how that identity heals or changes, and how we heal and change along with it.