Still: The Journal: Well, Crystal, when we made arrangements for this interview, you had not yet been appointed Kentucky’s Poet Laureate—the first Black woman ever to hold this prestigious appointment in Kentucky. We offer congratulations and our joy for you, so let’s start there before we talk more exclusively about your forthcoming book of poems, Perfect Black. What are some of your plans for Kentucky as its newest literary representative?

Crystal Wilkinson: First, let me say how excited and honored I am to be Kentucky Poet Laureate! As an ambassador of arts and letters for the state, I want to highlight the work of Kentucky writers of all genres and highlight writers that we don't often hear about. We are so fortunate to have such talented writers in Kentucky and I hope that over the course of the next two years that I can help shine a spotlight on them.

I also want to feature older writers across the state. There are so many senior citizens who are writing. Some of them are published but there are pockets of people who have been writing in silence and writing well for so long who have never gotten attention beyond their close circles. This idea is sparked in part by people like my Aunt Lovester who lives in Stanford, who self-published a book about her growing up in Lincoln County. It's a small book and just copied on a copy machine but it's so rich in culture and history. This idea is also inspired by a dear friend of mine, Mexie Cottle, who always wanted to be a writer and worked as a telephone operator for GE for years, then when she retired she started taking classes at the Carnegie Center and published her first book. She was in her 70s when she published it and received a grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women. There are so many paths to becoming a writer. I hope hearing these stories will encourage someone. And on the other end of that are Kentucky's youth writers. I hope to meet them too and to encourage them and highlight the work they are doing.

Still: As well as being Kentucky’s newest poet laureate, your novel, The Birds of Opulence, was chosen by the Kentucky Humanities Council as their 2021 Kentucky Reads Selection. The Humanities Council is encouraging and supporting book club discussions all around the Commonwealth. What does this selection mean for you as a writer? Are you hearing reports on those discussions or are book clubs reaching out to you?

CW: Wow. It's incredible. This has been a highlight of my career so far, especially as far as the state is concerned. There is nothing like recognition from home. I'm a Kentuckian through and through, and all of my writing stems from my heritage and ancestry that is rooted here in the Bluegrass, so this means so much. And yes, I'm hearing from some book clubs before they meet, but sometimes the conversation about the book happens and then I receive a warm note from the book club participants via email or social media or snail mail, and I just feel a wellspring of gratitude. Gratitude for my work receiving this recognition and gratitude that Kentucky readers are responding to the book so mightily.

So many of these conversations end up being about more than the book which I think is important. So many people are talking about the diversity of our state and since much of the book centers around mental illness, I've been told that many people are finding those sections of the book applicable to their lives and their families and mental wellness is being discussed which makes me very happy. I didn't write the book with the intent that it would be a tool for unpacking these silences, but I'm certainly pleased that it is being used to do this very necessary work of speaking about what silences us around discussions of mental wellness.

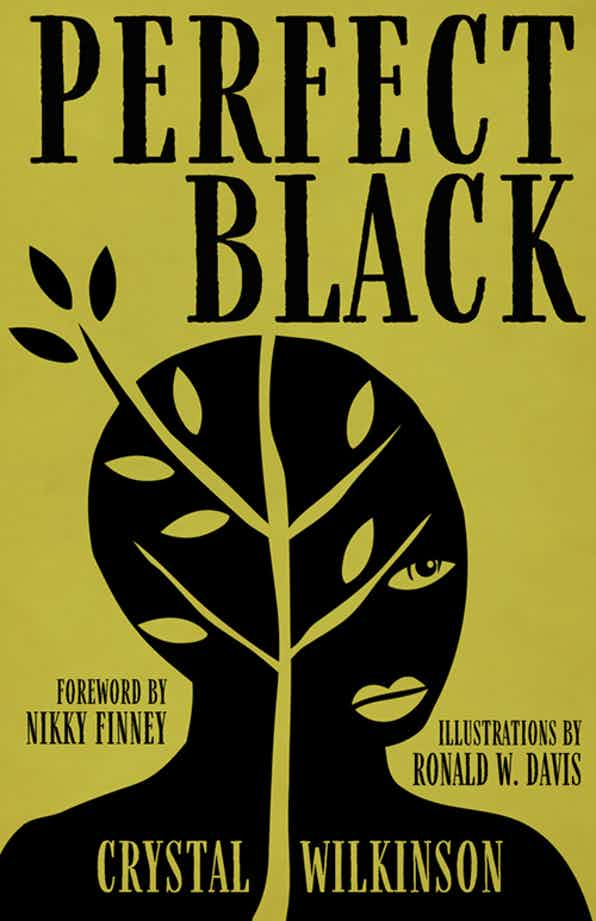

Still: So far we’ve mentioned two Kentucky institutions that foster the arts, so let’s bring in a third: your publisher, University Press of Kentucky. They’ll be bringing out your first published book of poems, Perfect Black, in August, 2021. In the introduction to Perfect Black, Nikky Finney writes: “Crystal Wilkinson’s writing life has always included poetry even though her book publishing life has not. As long as I’ve known her, she has held close the short-lined explosive form of expression.” What is it like for you, known primarily as a writer of short stories and novels, to be in the limelight as a poet?

CW: It's frightening. I love fiction. I love reading it and writing it, but, my love for poetry has always been strong, deep, and wide. And I've always written poetry, but outside a few poems that have been published, I've never had my own volume of poetry. I guess on some level I feel vulnerable. Even though a writer can do some exciting things with all the great things that the craft of poetry affords, there is really nowhere to hide. I take that back. There are lots of places to hide depending on where the poet stands in relation to their subject, but the hiding places are different than they are in fiction. In fiction, there are so many ways to bury a thread of truth, but in poetry the truth is there blazing in the light. And even if a reader doesn't know where the personal truth lies, because of the brevity of the form and the truth bearing of the form, it feels like a particular kind of exposure that I am not accustomed to. And I'm an open book, yet it feels different in my body. Not just confessional, because there's that too, but a kind of unlayering that I'm not used to.

Still: One of the concepts we have heard you talk about before is the notion of “ancestral memory,” sometimes called “genetic memory.” The phrase “ancestral memory” actually appears in “Terrain,” the first poem of the collection, and it’s evident in other poems, such as “Wet Nurse.” We also see the concept visually articulated, particularly in the appearances of the Sankofa. Could you explain “ancestral memory” in light of your work as writer, and specifically to your poetry?

CW: The writer A.J. Verdelle emphasizes that writers have things that haunt us—recurring thoughts, refrains, anxieties, situations, worries, etcetera. And sometimes writers will spend a lifetime walking about the same subjects and sometimes we write about a subject long enough that we sort of naturally let it go. The concept that I am more like my ancestors than I'm different from them, came to me at least 15 years ago and it's been a haunt since. I'm sort of obsessed with what we carry forward from earlier generations and what we leave behind—the things we can control, things we can't control.

When I look at a photograph of an ancestor and see my granddaughter, I'm flabbergasted at how genes work and how not just her smile was passed through DNA, but what mannerisms, what pathologies, what convictions are passed. Or are they passed? Are they learned? Are they passed through the blood? All of these things are poured into Perfect Black in some way, but this concept also informs my fiction and the nonfiction book that I just sold. I don't know if I will hold on to this concept for a while longer or if it will let me go. But we are headed toward twenty years and I'm still fascinated, not only in my work, but how it appears in the work of others. I think it adds a kind of emotional landscape or foundation to almost everything I do.