Interview

Interview with Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle

by Eliza Souers and Merritt Jenkins

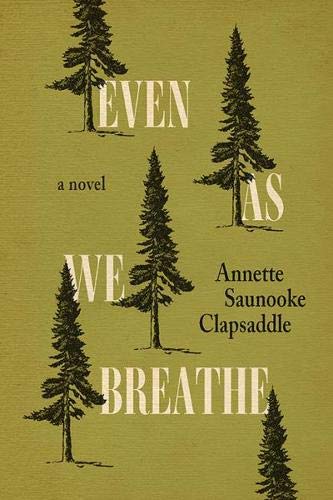

In September 2020, Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle released her debut novel, Even As We Breathe, through University Press of Kentucky. She read at Lee University for the Writer’s Series in the spring of 2021 and visited Lee’s advanced fiction writing class, at which time Lee University students Eliza Souers and Merritt Jenkins interviewed Clapsaddle on her new book and her writing style. They continued the interview via email.

Clapsaddle is an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and resides in Qualla, North Carolina with her husband and sons. She is a teacher at Swain County High School and serves on the board of trustees for the North Carolina Writers Network and used to serve as the executive director of the Cherokee Preservation Foundation and as a co-editor of the Journal of Cherokee Studies.

In addition to Even As We Breathe, Clapsaddle has written a novel manuscript, Going to Water, and has appeared in Yes! Magazine, Lit Hub, Smoky Mountain Living Magazine, South Writ Large, and The Atlantic.

According to Clapsaddle, Even As We Breathe is set during the summer of 1942 when the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina held foreign nationals as prisoners of war. The protagonist, Cowney Sequoyah (a young Cherokee man), leaves his grandmother Lishie, his uncle Bud, and his community in Cherokee to work as a member of the Inn’s grounds crew. He is joined by Essie Stamper, who, like Cowney, is trying to raise money for college. When Cowney is accused of being involved in the disappearance of a diplomat's daughter, he must work to clear his name, all the while unraveling the truth of his family's sordid past and choosing the path for his future. Even As We Breathe confronts issues of race, culture, identity, and citizenship.

The novel was a finalist for the Weatherford Award and named one of NPR’s Best Books of 2020. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution describes the novel as “a poignant story about loss and home, how a person who has never known their parents finds a way to reckon with their roots and their history, and how the truth, no matter how painful it may be, can pave the way to peace.”

. . . As my editor is fond of reminding me, I have to ask, “Where’s the trouble?” in each scene if I want that scene to propel the reader forward. I am constantly asking myself if there is enough tension in a scene.

Clapsaddle: In the original draft, the title was explicitly stated in the last paragraph. My editor and I chose to take it out as it was too overt. It is a reference to the importance of the human spirit over bones, blood, and skin. Even as we breathe, we still fixate on these qualities, which means that we overlook the essential aspect of our existence while trying to find other reasons to exclude others. References are intentionally peppered throughout the novel to help bolster this message.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________