Interview

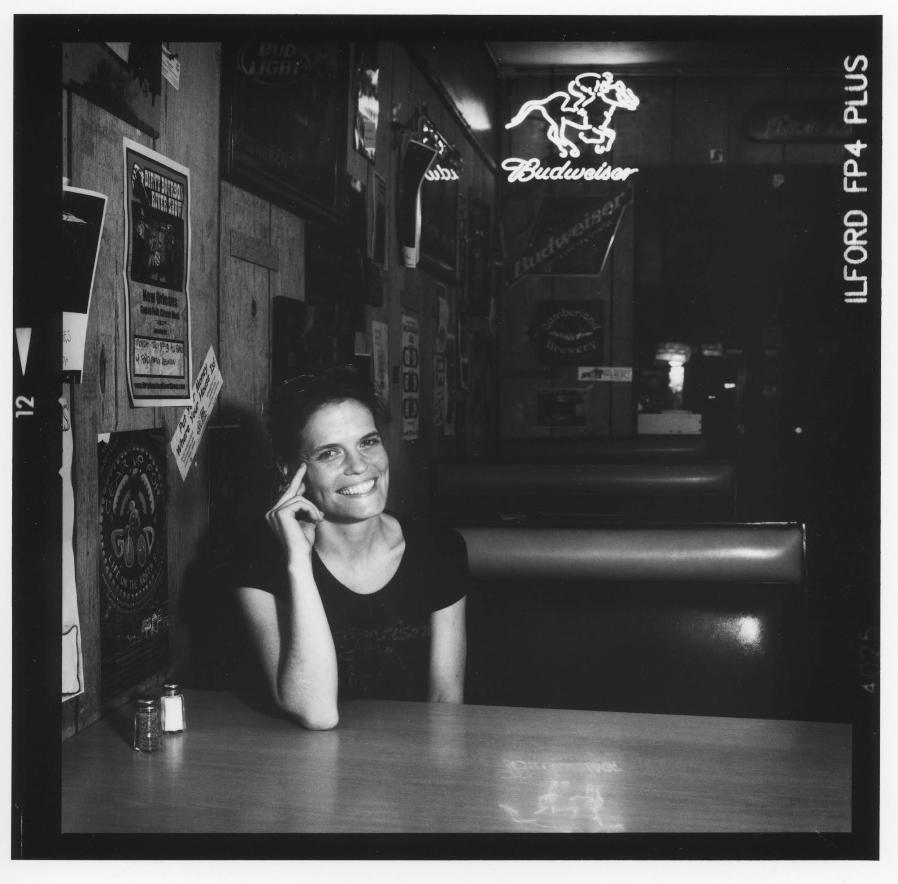

Interview with Rebecca Gayle Howell

© Guy Mendes. Used with permission.

Rebecca Gayle Howell is a poet who cares deeply about most things, but particularly about three things that we at Still: The Journal hold dear: words, community, dogs. In the following conversation, Still fiction editor Silas House sat down with Howell, and they examined all of those things, and much more. The conversation was also recently broadcast on Silas’s radio show Hillbilly Solid to a wide audience. Here we offer a condensed transcript of their visit. But first, more about Rebecca Gayle Howell.

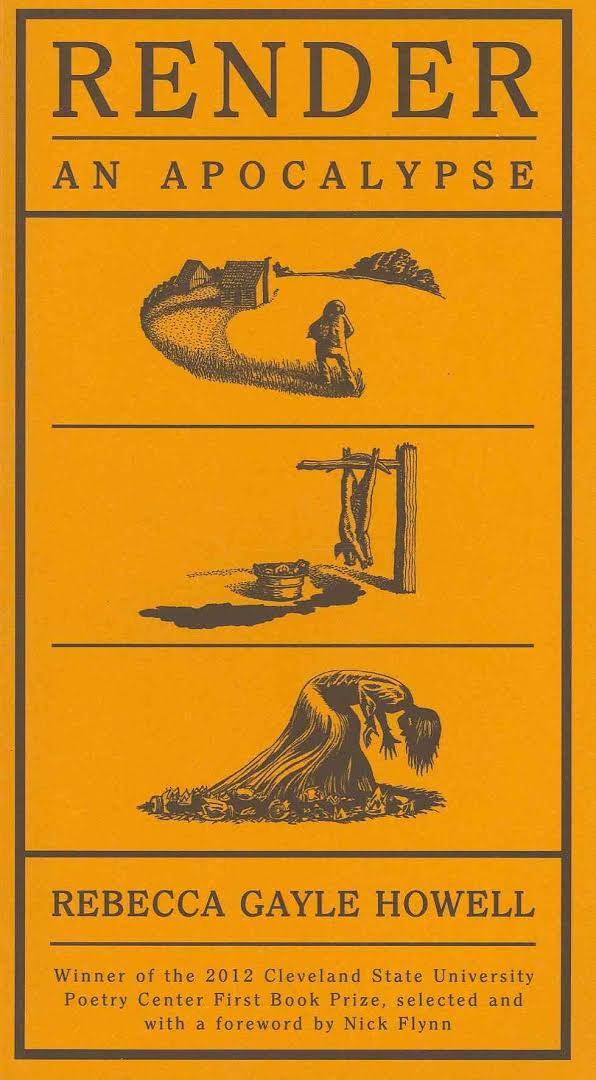

Rebecca is the author of Render /An Apocalypse (2013), which was selected by Nick Flynn for the Cleveland State University First Book Prize and was a 2014 finalist for ForeWord Review's Book of the Year and the 2014 Weatherford Award for Best Appalachian Book of Poetry. She is also the translator of Amal al-Jubouri's Hagar Before the Occupation/Hagar After the Occupation (Alice James Books, 2011), which was named a 2011 Best Book of Poetry by Library Journal and shortlisted for Three Percent's 2012 Best Translated Book Award. Among her awards are fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and the Carson McCullers Center, as well as a 2014 Pushcart Prize.

She is a native of Kentucky and currently lives in Lexington.

Still: Was there one poem you can pinpoint that just changed your world? Or one poet?

RGH: I did love Dickinson early on and I did love Eliot early on – Four Quartets still really blows me away.

Still: Did you train with particular poets and writers who really had an impact on you?

RGH: I’ve been really fortunate in my apprenticeship, I should say. My first teacher was Nikki Finney. My first mentor was James Baker Hall. But I’ve gone on to be mentored and taught by Alicia Ostriker, Gerald Stern, Jean Valentine. I’ve just been a really lucky girl.

Still: Finney and Hall have a Kentucky connection, and you’re a native of Kentucky, but how did you get to know other poets across the country?

RGH: Well, I did my MFA low-residency so I did the unusual thing that a lot of writers forget to do which is, pick writers I wanted to be mentored by and then go to their program. So I went to the program Gerald Stern put together in New Jersey called Drew University and I lived in Kentucky and worked my job at Morehead [State University] and through that program I worked with the best translators and poets in America. I received a phenomenal education and after that I was fortunate enough to receive a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center. Provincetown is the only other community of what we have here. Long tradition of high literary standards and high generosity. It’s about the work.

Still: What do you want the readers of Still to know about Render / An Apocalypse.

RGH: Render is a southern agrarian myth. There are two characters you need to know. There’s a protagonist who wakes up in the real world that he’s forgotten how to survive in and there’s the narrator who is – I imagine her as a woman, but she’s not necessarily – and she’s a trickster narrator. So sometimes she’s giving him advice about how to survive that’s trustworthy, and sometimes she’s requiring him to learn the hard way.

Still: How does a poet set out to write a collection like this? A collection wherein one poem is dependent on another poem. In Render, everything works together, so could you talk a little bit about that process?

RGH: I think that all collections of poetry, as you say, dovetail, and the poems – like dominos – depend on each other. But I think there’s a way you can collect poems that you’ve written over a period of time, and in the middle part of the twentieth century poets would just put the dates between which of these poems were written. I like the term: a book of poems. So a book like Render or Maurice Manning’s Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions, is a book that has poems that stand on their own, but they also collaborate with each other on such a deep level it almost becomes a book-length poem itself. I would say Render is in that category. Now, how I set out to write it. I did not say, “Oh. Let’s do this.” I just, honestly, heard the first poem and then the next. Eventually there were five or six of these "How to" poems and I realized that they were poems that were giving advice both on the corporeal land-living level and also on a spiritual, emotional level. It wasn’t until about three quarters of the way through the manuscript writing that I realized it was a myth.

Still: Your poem “How to Kill A Hog” ends with the line “do not turn away”. Would you agree that that’s the mantra of most writers, the demand to always observe, to be conscious?

RGH: I think the good ones don’t turn away. I’ll say that. And I think that the writing life can welcome a practice of opening your practice, opening your awareness or passion, opening your mind to new ways of thinking. I mentioned Alicia Ostriker earlier. She still is mentoring me. She’s a special soul. She always says that one of the sacred teachings of the Torah is: “turn it, turn it, for all is in it.” And that’s so different from what American Christians are taught about their scripture. “Turn it, turn it, for all is in it,” meaning: get in there and wrestle with it. And I think that the writing practice – the writing life – invites us to do that to our own lives, our communities, our politics, our living world.

Still: An interesting pair of your poems to look at is “How to Kill a Rooster” and “How to Kill a Hen." Can you talk about how those complement each other?

RGH: I hate the word “theme,” but one of the things I was worried about and thinking about when I was writing was climate change. I was reading a lot of Wendell Berry that winter and, just thinking about what got us into this situation. It seemed to me that it has a lot to do with our quest for dominance. In the individual, as well as the whole species, you know? Our willingness and our desire to dominate each other. I think that as a woman and as a feminist, it seems pretty clear to me that women are globally dominated and it’s still a crisis that we must not turn away from. So, much of Render talks about that instinct to dominate in gender roles. So “How to Kill a Rooster” is a revenge poem. This is a woman who has been spurred. I was a woman who had been spurred and I was angry when I wrote this poem. I think that in the larger myth the consequences are clear. Now “How to Kill a Hen” is the same story told from a different perspective and I think, you know, even though I’ve been spurred as a woman, and even though I do think it is a global crisis of dominating women particularly, I think we do to each other and I think the woman inside all of us – inside every man and woman – is also often dominated. We try to snuff that out too. So that’s a lot of what’s going on in that poem.

Still: While there is definitely this theme of dominance, there is also a tenderness throughout the book, especially in a poem like “How to Be An Animal."

RGH: The anecdote that the poems led me to and that the myth leads to eventually in the book, is tenderness and touch. And not just mental kindness that we give each other—which is important--but physical kindness that, at an animal level, really matters. For me the answer is remembering that I am an animal first, that my mind is all over my body not just up in my skull. When my dog, Key, wants what she wants, she’ll saddle up to me, she’ll lean on me, she’ll wag her tail. She’s all physical communication. And pigs are very much like that. They love to be touched. They love tenderness.

Still: It’s ironic that so many animals suffer in this book because you’re such an animal lover and anybody who knows you knows that you and Key are inseparable. It seems that so many writers and artists are such animal lovers and especially have an affinity for dogs.

RGH: I think my dog, Key, has been a real teacher to me. Not just in the tenderness I just talked about and opening myself up to that and to physical communication but also—boy, a dog will teach you about boundaries real quick. They need them, they want them, and so do we, frankly. I think that they offer a level of intimacy that writers—good writing happens in community but we have to hole up and write. It can be not necessarily a lonely life but it can be an alone life and dogs make up a big lot for that.

Still: You serve as poetry editor for Oxford American, one of those magazines that everyone wants to be in, so tell us about that.

RGH: I joined Oxford American—I still feel surprised that I’m their poetry editor—after they asked me for new work. They published a handful of poems and our conversation grew, we all liked each other, and they asked me to be the magazine’s poetry editor. We get a lot of submissions and I solicit work. Oxford American is a magazine that everyone wants to read. Our average circulation is 30,000; that’s a lot of people who want a good read, and I love bringing poetry to them. But as a Southern writer myself and as someone who’s thought a lot about place and community and how important those things are to what it means to be a writer, I take it very seriously to edit poems that say something about what it means to be a Southern poet.

Still: Are you working on a new book?

RGH: Well, as I said, Oxford American asked for new work and Render had just come out and I didn’t have any new work but it was Oxford American! So I started writing my tush off and these poems are what came. They accepted all of them—thank you, Roger Hodge—and they are part of what will now be my second book. It’s with publishers now. It’s also a Southern myth. This one considers closely issues of economic exploitation and what it means to be poor in America.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview Still Life

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Contest Masthead Submit Feedback

_____________________________________________